-

LDS Church Accused of Tax Fraud

TThe Mormon ObserverOct 30, 2022 #60MinutesAustralia Subscribe here: http://9Soci.al/chmP50wA97J Full Episodes: https://9now.app.link/uNP4qBkmN6 | Cooking the Book of Mormon (2022) Once famous – or infamous – for its stance on polygamy, these days the Mormon Church is better known for its earnest young missionaries who doorknock our suburbs promising enlightenment. But on 60 MINUTES, enlightenment about a subject the Mormon Church wants to keep secret: serious accusations that Mormons in Australia have been able to draw on $400 million in tax deductions not lawfully available to followers of other religions. It’s alleged by church whistle-blowers that the Mormon books are being cooked in an elaborate tax dodge. As Tom Steinfort reports, this is money Australia could well use, but despite the federal government’s bluster about cracking down on waste and rorting, so far it has done nothing.51 views -

Joseph Smith: The Prophet of the Restoration (2005)

TThe Mormon ObserverJoseph Smith: The Prophet of the Restoration is a 2005 film that focuses on some of the events during the life of Joseph Smith, founder of the Latter Day Saint movement, which was both filmed and distributed by the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS Church). The film was shown in the Legacy Theater of the Joseph Smith Memorial Building from its opening on December 17, 2005 until early 2015, and opened in several LDS Church visitors' centers on December 24, 2005. The film used the digital intermediate process. In March 2011, the church released a revised cut of the film, which is available to watch in select visitors' centers and online. Additionally, the church has released the film in several languages including ASL, Spanish, French, German, and Japanese.79 views -

America Unearthed: Ancient Mayans Secrets in Georgia - S01E01

The American ObserverJun 28, 2020 #AmericaUnearthed Geologist and adventurer Scott Wolter explores a government-restricted site, and makes a startling discovery connecting the ancient Mayans with rural Georgia, in Season 1, Episode 1, "American Maya Secret". #AmericaUnearthed Subscribe for more from America Unearthed and other great HISTORY shows: http://histv.co/SubscribeHistoryYT Find out more about the show and watch full episodes on our site: http://www.history.com/shows/ Check out exclusive HISTORY content: History Newsletter - www.history.com/newsletter Website - http://www.history.com Facebook - / history Twitter - / history In "America Unearthed," host Scott Wolter uses hard science and intuitive theories to explain the most mysterious artifacts and sites in America. HISTORY® is the leading destination for award-winning original series and specials that connect viewers with history in an informative, immersive, and entertaining manner across all platforms. The network's all-original programming slate features a roster of hit series, premium documentaries, and scripted event programming. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=C2w-WSl3NN8165 views

The American ObserverJun 28, 2020 #AmericaUnearthed Geologist and adventurer Scott Wolter explores a government-restricted site, and makes a startling discovery connecting the ancient Mayans with rural Georgia, in Season 1, Episode 1, "American Maya Secret". #AmericaUnearthed Subscribe for more from America Unearthed and other great HISTORY shows: http://histv.co/SubscribeHistoryYT Find out more about the show and watch full episodes on our site: http://www.history.com/shows/ Check out exclusive HISTORY content: History Newsletter - www.history.com/newsletter Website - http://www.history.com Facebook - / history Twitter - / history In "America Unearthed," host Scott Wolter uses hard science and intuitive theories to explain the most mysterious artifacts and sites in America. HISTORY® is the leading destination for award-winning original series and specials that connect viewers with history in an informative, immersive, and entertaining manner across all platforms. The network's all-original programming slate features a roster of hit series, premium documentaries, and scripted event programming. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=C2w-WSl3NN8165 views -

The REAL Story of the Mormon Church - Full Documentary

derekwsparksAug 9, 2023 Understanding the roots of the Latter-day Saints. Go to our sponsor https://betterhelp.com/johnnyharris for 10% off your first month of therapy with BetterHelp and get matched with a therapist who will listen and help. Joseph Smith grew from a treasure hunting farm kid in Upstate New York, to the prophet and founder of the LDS Church. This is a story of American expansion, persecution, and a gifted storyteller. My next video is live on Nebula NOW! It's about the biggest national security risk you've never heard of -- submarine cables. Watch now: https://nebula.tv/videos/johnnyharris... Check out all my sources for this video here: https://docs.google.com/document/d/1r... Get access to behind-the-scenes vlogs, my scripts, and extended interviews over at / johnnyharris Do you have an insider tip or unique information on a story? Do you have a suggestion for a story you want us to cover? Submit to the Tip Line: https://docs.google.com/forms/d/e/1FA... Check out our newest channel Search Party with Sam Ellis: / @search-party I made a poster about maps - check it out: https://store.dftba.com/products/all-... Custom Presets & LUTs [what we use]: https://store.dftba.com/products/john... The music for this video, created by our in house composer Tom Fox, is available on our music channel, The Music Room! Follow the link to hear this soundtrack and many more: • Joseph Smith | Original Soundtrack | ... About: Johnny Harris is an Emmy-winning independent journalist and contributor to the New York Times. Based in Washington, DC, Harris reports on interesting trends and stories domestically and around the globe, publishing to his audience of over 3.5 million on Youtube. Harris produced and hosted the twice Emmy-nominated series Borders for Vox Media. His visual style blends motion graphics with cinematic videography to create content that explains complex issues in relatable ways. - press - NYTimes: https://www.nytimes.com/2021/11/09/op... NYTimes: https://www.nytimes.com/video/opinion... Vox Borders: • Inside Hong Kong’s cage homes NPR Planet Money: https://www.npr.org/transcripts/10721... - where to find me - Instagram: / johnny.harris Tiktok: / johnny.harris Facebook: / johnnyharrisvox Iz's (my wife’s) channel: / iz-harris - how i make my videos - Tom Fox makes my music, work with him here: https://tfbeats.com/ I make maps using this AE Plugin: https://aescripts.com/geolayers/?aff=77 All the gear I use: https://www.izharris.com/gear-guide - my courses - Learn a language: https://brighttrip.com/course/language/ Visual storytelling: https://www.brighttrip.com/courses/vi... https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hUW7j9GmXjI143 views

derekwsparksAug 9, 2023 Understanding the roots of the Latter-day Saints. Go to our sponsor https://betterhelp.com/johnnyharris for 10% off your first month of therapy with BetterHelp and get matched with a therapist who will listen and help. Joseph Smith grew from a treasure hunting farm kid in Upstate New York, to the prophet and founder of the LDS Church. This is a story of American expansion, persecution, and a gifted storyteller. My next video is live on Nebula NOW! It's about the biggest national security risk you've never heard of -- submarine cables. Watch now: https://nebula.tv/videos/johnnyharris... Check out all my sources for this video here: https://docs.google.com/document/d/1r... Get access to behind-the-scenes vlogs, my scripts, and extended interviews over at / johnnyharris Do you have an insider tip or unique information on a story? Do you have a suggestion for a story you want us to cover? Submit to the Tip Line: https://docs.google.com/forms/d/e/1FA... Check out our newest channel Search Party with Sam Ellis: / @search-party I made a poster about maps - check it out: https://store.dftba.com/products/all-... Custom Presets & LUTs [what we use]: https://store.dftba.com/products/john... The music for this video, created by our in house composer Tom Fox, is available on our music channel, The Music Room! Follow the link to hear this soundtrack and many more: • Joseph Smith | Original Soundtrack | ... About: Johnny Harris is an Emmy-winning independent journalist and contributor to the New York Times. Based in Washington, DC, Harris reports on interesting trends and stories domestically and around the globe, publishing to his audience of over 3.5 million on Youtube. Harris produced and hosted the twice Emmy-nominated series Borders for Vox Media. His visual style blends motion graphics with cinematic videography to create content that explains complex issues in relatable ways. - press - NYTimes: https://www.nytimes.com/2021/11/09/op... NYTimes: https://www.nytimes.com/video/opinion... Vox Borders: • Inside Hong Kong’s cage homes NPR Planet Money: https://www.npr.org/transcripts/10721... - where to find me - Instagram: / johnny.harris Tiktok: / johnny.harris Facebook: / johnnyharrisvox Iz's (my wife’s) channel: / iz-harris - how i make my videos - Tom Fox makes my music, work with him here: https://tfbeats.com/ I make maps using this AE Plugin: https://aescripts.com/geolayers/?aff=77 All the gear I use: https://www.izharris.com/gear-guide - my courses - Learn a language: https://brighttrip.com/course/language/ Visual storytelling: https://www.brighttrip.com/courses/vi... https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hUW7j9GmXjI143 views -

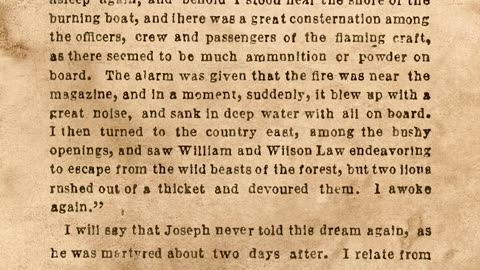

W. W. Phelps - Joseph Smith's Last Dream

TThe Mormon ObserverHis dream of coming to Heaven. Two days before his martyrdom, Joseph Smith told W. W. Phelps about a prophetic dream he had a few nights prior. W. W. Phelps did not publish the account until 1862, but when he did, he titled it: "Joseph Smith's Last Dream." Joseph Smith, the founder and leader of the Latter Day Saint movement, and his brother, Hyrum Smith, were killed by a mob in Carthage, Illinois, United States, on June 27, 1844, while awaiting trial in the town jail. As mayor of the city of Nauvoo, Illinois, Joseph Smith had ordered the destruction of the facilities used to print the Nauvoo Expositor, a newly-established newspaper created by a group of non-Mormons and others who had seceded from Smith's church, the Church of Christ. The newspaper's first (and only) issue was highly critical of Smith and other church leaders, reporting that Smith was practicing polygamy and claiming he intended to set himself up as a theocratic king. In response, a motion to declare the newspaper a public nuisance was passed by the Nauvoo City Council, and Smith consequently ordered its press destroyed.[1] The destruction of the press led to public outrage, and the Smith brothers and other members of the Nauvoo City Council were charged with inciting a riot. Warrants for Joseph Smith's arrest were dismissed by Nauvoo courts. Smith declared martial law in Nauvoo and called on the Nauvoo Legion to protect the city. After briefly fleeing Illinois, Smith returned and, along with Hyrum, voluntarily traveled to the county seat at Carthage to face the charges. After surrendering to authorities, the brothers were also charged with treason against Illinois for declaring martial law. The Smith brothers were detained at Carthage Jail awaiting trial when an armed mob of 150–200 men stormed the building, their faces painted black with wet gunpowder. Hyrum was killed almost immediately when he was shot in the face, shouting as he fell, "I am a dead man!"[2] After emptying his pistol towards the attackers, Joseph tried to escape from a second-story window, but was shot several times and fell to the ground, where he was shot again by the mob. Five men were indicted for the killings, but were acquitted at a jury trial. At the time of his death, Smith was also running for president of the United States,[3] making him the first U.S. presidential candidate to be assassinated. Smith's death marked a turning point for the Latter Day Saint movement, and since then, Latter Day Saints have generally viewed him and his brother as religious martyrs who were "murdered in cold blood".[4] This article is part of a series on Joseph Smith 1805 to 18271827 to 18301831 to 18371838 to 18391839 to 1844 DeathLegalPolygamyWivesChildrenTeachingsMiraclesPropheciesBibliographyChronology OutlineCategory Latter Day Saints portal vte Background A monument to Joseph and Hyrum Smith, entitled Last Ride, is in front of the Nauvoo Illinois Temple Followers of the Latter Day Saint movement began to move into Hancock County, Illinois, in 1839; at the time, most supported the Democratic Party. After their expulsion from the neighboring state of Missouri during the 1838 Mormon War, the Latter Day Saint movement's founder, Joseph Smith, travelled to Washington, D.C., to meet with President Martin Van Buren, seeking intervention and compensation for lost property. Van Buren said he could do nothing to help. Smith returned to Illinois and vowed to join the Whig Party. Most of his supporters switched with him, adding political tensions to the social suspicions in which Smith's followers were held by the local populace.[5] Nauvoo Expositor Main article: Nauvoo Expositor Several of Smith's disaffected associates in Hancock County and in the city of Nauvoo, Illinois, where Smith was mayor, joined together to publish a newspaper called the Nauvoo Expositor, which put out its first and only issue on June 7, 1844.[6]: v6, p430 Based on allegations by some of these associates, the Expositor reported that Smith practiced polygamy and that he tried to marry the wives of some of his associates. The newspaper further reported that eight of Smith's wives had already been married to other men (four were Latter Day Saints in good standing, who in a few cases acted as witnesses in Smith's marriage to his first wife) at the time they married Smith. Typically, these women continued to live with their first husbands, not Smith. Some accounts say Smith may have had sexual relations with one wife, who later in her life stated that he fathered children by one or two of his wives.[7] The reliability of these sources is disputed by some Mormons.[8] In response to public outrage generated by the Expositor, the Nauvoo City Council passed an ordinance declaring the newspaper a public nuisance which had been designed to promote violence against Smith and his followers. They reached this decision after some discussion, including citation of William Blackstone's legal canon, which defined a libelous press as a public nuisance. According to the Council's minutes, Smith said he "would rather die tomorrow and have the thing smashed, than live and have it go on, for it was exciting the spirit of mobocracy among the people, and bringing death and destruction upon us."[9] Under the Council's new ordinance, Smith, as Nauvoo's mayor, in conjunction with the Council, ordered the city marshal to destroy the Expositor and its printing press on June 10, 1844. By the city marshal's account, the destruction of the press type was carried out orderly and peaceably. However, Charles A. Foster, a co-publisher of the Expositor, reported on June 12 that not only was the printing press destroyed, but that "several hundred minions ... injured the building very materially".[10] Smith's critics said that the action of destroying the press violated freedom of the press. Some sought legal charges against Smith for the destruction of the press, including charges of treason and inciting a riot. Violent threats were made against Smith and the Latter Day Saints. Thomas C. Sharp, editor of the Warsaw Signal in Warsaw, Illinois, a newspaper hostile to the church, editorialized:[11] War and extermination is inevitable! Citizens ARISE, ONE and ALL!!!—Can you stand by, and suffer such INFERNAL DEVILS! To ROB men of their property and RIGHTS, without avenging them. We have no time for comment, every man will make his own. LET IT BE MADE WITH POWDER AND BALL!!! Incarceration at Carthage Jail See also: Joseph Smith and the criminal justice system An etching of the Carthage Jail, c. 1885 Warrants from outside Nauvoo were brought in against Smith and dismissed in Nauvoo courts on a writ of habeas corpus. Smith declared martial law on June 18[12] and called out the Nauvoo Legion, an organized city militia of about 5,000 men,[13] to protect Nauvoo from outside violence.[12] In response to the crisis, Illinois Governor Thomas Ford traveled to Hancock County, and on June 21 he arrived at the county seat in Carthage. On June 22, Ford wrote to Smith and the Nauvoo City Council, proposing a trial by a non-Mormon jury in Carthage and guaranteeing Smith's safety. Smith fled the jurisdiction to avoid arrest, crossing the Mississippi River into the Iowa Territory. On June 23, a posse under Ford's command entered Nauvoo to execute an arrest warrant, but they were unable to locate Smith. After he was criticized by some followers, Smith returned and was reported to have said, "If my life is of no value to my friends it is of none to myself."[6]: v6, p549 He reluctantly submitted to arrest. He was quoted as saying, "I am going like a lamb to the slaughter; but I am calm as a summer's morning; I have a conscience void of offense towards God, and towards all men. I shall die innocent, and it shall yet be said of me—he was murdered in cold blood."[14] During the trip to Carthage, Smith reportedly recounted a dream in which he and Hyrum escaped a burning ship, walked on water, and arrived at a great heavenly city.[15] On June 25, 1844, Smith and his brother Hyrum, along with the other fifteen Council members and some friends, surrendered to Carthage constable William Bettisworth on the original charge of riot. Upon arrival in Carthage, almost immediately the Smith brothers were charged with treason against the State of Illinois for declaring martial law in Nauvoo, by a warrant founded upon the oaths of A. O. Norton and Augustine Spencer. At a preliminary hearing that afternoon, the Council members were released on $500 bonds, pending later trial. The judge ordered the Smith brothers to be held in jail until they could be tried for treason, which was a capital offense.[citation needed] Smuggled gun used by Smith to shoot Wills, Vorhease, and Gallaher[16] The Smith brothers were detained at Carthage Jail, and were soon joined by Willard Richards, John Taylor and John Solomon Fullmer. Six other associates accompanied the Smiths: John P. Greene, Stephen Markham, Dan Jones, John S. Fullmer, Dr. Southwick, and Lorenzo D. Wasson.[17] Ford left for Nauvoo not long after Smith was jailed. The anti-Mormon[5] "Carthage Greys", a local militia, were assigned to protect the brothers. Jones, who was present, relayed to Ford several threats against Joseph made by members of the Greys, all of which were dismissed by Ford.[18] On Thursday morning, June 27, church leader Cyrus Wheelock, having obtained a pass from Ford, visited Smith in jail. The day was rainy, and Wheelock used the opportunity to hide a small pepper-box pistol in his bulky overcoat,[19] which had belonged to Taylor.[20] Most visitors were rigidly searched,[21] but the guards forgot to check Wheelock's overcoat,[22] and he was able to smuggle the gun to Smith. Smith took Wheelock's gun and gave Fullmer's gun to his brother Hyrum. Attack The door in Carthage Jail through which the mob fired. There is a bullet hole in the door. Hit by a ball, Smith fell from the second story window Before a trial could be held, a mob of about 200 armed men, their faces painted black with wet gunpowder, stormed Carthage Jail in the late afternoon of June 27, 1844. As the mob was approaching, the jailer became nervous and informed Smith of the impending attack. In a letter dated July 10, 1844, one of the jailers wrote that Smith, expecting the Nauvoo Legion, said, "Don't trouble yourself ... they've come to rescue me."[23] Smith did not know that Jonathan Dunham, major general of the Nauvoo Legion, had not dispatched the unit to Carthage to protect him. Allen Joseph Stout later contended that by remaining inactive, Dunham disobeyed an official order written by Smith after he was jailed in Carthage.[24] The Carthage Greys reportedly feigned defense of the jail by firing shots or blanks over the attackers' heads, and some of the Greys even reportedly joined the mob, who rushed up the stairs.[23] The mob first attempted to push the door open to fire into the room, though Smith and the other prisoners pushed back and prevented this. A member of the mob fired a shot through the door. Hyrum was shot in the face, just to the left of his nose, which threw him to the floor. He cried out, "I am a dead man!" and collapsed. He died instantly.[25] Smith, Taylor, and Richards attempted to defend themselves. Taylor and Richards used a long walking stick in order to deflect the guns as they were thrust inside the room, from behind the door. Smith fired Wheelock's pistol.[26] Three of the six barrels misfired,[27] but the other three shots are believed to have wounded three of the attackers.[28][29] Taylor was shot four or five times and was severely wounded, but survived. It has been popularly believed that his pocket watch stopped one shot. The watch is displayed in the LDS Church History Museum in Salt Lake City, Utah; the watch was broken and was used to help identify the time of the attack. In 2010, forensic research by J. Lynn Lyon of the University of Utah and Mormon historian Glen M. Leonard suggested that Taylor's watch was not struck by a ball, but rather broke against a window ledge.[30] Columbia University historian Richard Bushman, the author of Joseph Smith: Rough Stone Rolling, also supports this view. Pocket watch worn by John Taylor during the killings of Joseph and Hyrum Smith. Richards, physically the largest of Smith's party, escaped unscathed; Lyon speculates that after the door opened, Smith was in the line of sight and Richards was not targeted.[31] After using all of the shots in his pistol, Smith made his way towards the window. As he prepared to jump down, Richards reported that he was shot twice in the back and that a third bullet, fired from a musket on the ground outside, hit him in the chest.[6]: v6, p620 Taylor and Richards' accounts both report that as Smith fell from the window, he called out, "Oh Lord, my God!" Some have alleged that the context of this statement was an attempt by Smith to use a Masonic distress signal.[32] 1851 lithograph of Smith's body being mutilated. (Library of Congress) There are varying accounts of what happened next. Taylor and Richards' accounts state that Smith was dead when he hit the ground. Eyewitness William Daniels wrote in his 1845 account that Smith was alive when members of the mob propped his body against a nearby well, assembled a makeshift firing squad, and shot him before fleeing. Daniels' account also states that one man tried to decapitate Smith for a bounty but was prevented by divine intervention. That affirmation later was denied.[33] Additional reports said that thunder and lightning frightened off the mob.[34] Mob members fled, shouting, "The Mormons are coming," although there was no such force nearby.[35] After the attack was over, Richards, who was trained as a medical doctor, went back to see if anyone besides himself had survived, and found Taylor lying on the floor. Richards dragged Taylor into the jail cell (they had not been held in the cell, but in the guard's room across the hallway). He dragged Taylor under some of the straw mattress to put pressure on his wounds and slow the bleeding and then went to get help. Both Richards and Taylor survived. Taylor eventually became the third president of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS Church). Richards had escaped all harm except for a bullet grazing his ear. Joseph's younger brother Samuel Harrison Smith had come to visit the same day and, after evading capture from a group of attackers, is said to have been the first Latter Day Saint to arrive and helped attend the bodies back to Nauvoo. He died thirty days later, possibly as a result of injuries sustained avoiding the mob.[36] Side of Carthage Jail, c. 1890, showing the well Injuries to mob members There have been conflicting reports about injuries to members of the mob during the attack, and whether any died. Shortly after the events occurred, Taylor wrote that he heard that two of the attackers died when Smith shot them with his pistol.[6]: v7, p102 Most accounts seem to agree that at least three attackers were wounded by Smith's gunfire, but there is no other evidence that any of them died as a result. John Wills was shot in the arm, William Vorhease was shot in the shoulder, and William Gallaher was shot in the face.[37][38] Others claimed that a fourth unnamed man was also wounded.[38] Wills, Vorhease, Gallaher, and a Mr. Allen (possibly the fourth man) were all indicted for the murder of the Smith brothers. Wills, Vorhease, and Gallaher, perhaps conscious that their wounds could prove that they were involved in the mob, fled the county after being indicted and were never brought to trial.[39] Apart from Taylor's report of what he had heard, there is no evidence that Wills, Vorhease, Gallaher, or Allen died from their wounds.[40] Interment See also: Smith Family Cemetery Joseph and Hyrum Smith's bodies were returned to Nauvoo the next day. The bodies were cleaned and examined, and death masks were made, preserving their facial features and structures. A public viewing was held on June 29, 1844, after which empty coffins weighted with sandbags were used at the public burial. (This was done to prevent theft or mutilation of the bodies.) The coffins bearing the bodies of the Smith brothers were initially buried under the unfinished Nauvoo House, then disinterred and deeply reburied under an out-building on the Smith homestead. In 1928, Frederick M. Smith, president of the Reorganized Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints (RLDS Church) and grandson of Joseph Smith, feared that rising water from the Mississippi River would destroy the grave site. He authorized civil engineer William O. Hands to conduct an excavation to find the Smiths' bodies. Hands conducted extensive digging on the Smith homestead and located the bodies, as well as finding the remains of Joseph's wife, Emma, who was buried in the same place. The remains—which were badly decomposed—were examined and photographed, and the bodies were reinterred close by in Nauvoo. Current gravesite of Joseph, Hyrum, and Emma Smith Current gravesite of Joseph, Hyrum, and Emma Smith Death Mask of Hyrum Smith. Note the bullet hole to the left of his nose. Death Mask of Hyrum Smith. Note the bullet hole to the left of his nose. Death Mask of Joseph Smith. Death Mask of Joseph Smith. Responsibility and trial After the killings, there was speculation about who was responsible. Ford denied accusations that he knew about the plot to kill Smith beforehand, but later wrote that it was good for Smith's followers to have been driven out of the state and said that their beliefs and actions were too different to have survived in Illinois. He said Smith was "the most successful impostor in modern times,"[41] and that some people "expect more protection from the laws than the laws are able to furnish in the face of popular excitement."[42] Ultimately, five defendants—Thomas C. Sharp, Mark Aldrich, William N. Grover, Jacob C. Davis and Levi Williams—were tried for the murders of the Smith brothers. All five defendants were acquitted by a jury, which was composed exclusively of non-Mormon members after the defense counsel convinced the judge to dismiss the initial jury, which did include Mormon members.[43] The defense was led by Orville Hickman Browning, later a United States senator and cabinet member. [44] Consequences in the Latter Day Saint movement This section needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources in this section. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. Find sources: "Killing of Joseph Smith" – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (June 2017) (Learn how and when to remove this message) Main articles: Succession crisis (Latter Day Saints) and Apostolic succession (LDS Church) After the killing of Smith, a succession crisis occurred in the Latter Day Saint movement. Hyrum Smith, the Assistant President of the Church, was intended to succeed Joseph as President of the Church,[45] but because he was killed alongside his brother, the proper succession procedure became unclear. Initially, the primary contenders to succeed Smith were Sidney Rigdon, Brigham Young, and James Strang. Rigdon was the senior surviving member of the First Presidency, a body that had led the Latter Day Saint movement since 1832. At the time of Smith's death, he was estranged from Smith due to differences in doctrinal beliefs. Young, president of the Quorum of the Twelve, claimed authority was handed by Smith to the Quorum. Strang claimed that Smith designated him as the successor in a letter that was received a week before his death. Later, others came to believe that Smith's son, Joseph Smith III, was the rightful successor under the doctrine of lineal succession. A schism resulted, with each claimant attracting followers. The majority of Latter Day Saints followed Young; these adherents later emigrated to what became Utah Territory and continued as the LDS Church. Rigdon's followers were known as Rigdonites, some of which later established The Church of Jesus Christ (Bickertonite). Strang's followers established the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints (Strangite). In the 1860s, those who felt that Smith should have been succeeded by Joseph Smith III established the RLDS Church, which later changed its name to the Community of Christ.81 views -

The Lamanites of the Ancient Great Plains

TThe Mormon ObserverThe Great Plains are well-known for their indigenous traditions but also have a rich history that spans over ten thousand years. Contrary to what some people think, the plains were not a backwater but a rich and flourishing area with a diverse array of cultures that drew in outside influence and people and interacted with their neighbors. Join us as we explore the pre-columbian history of the Great Plains. Chapters: Introduction: 0:00 Paleoindians on the Plains: 5:42 Archaic Plains Period: 14:43 Plains Woodland: 24:14 Plains Village Period: 32:58 Conclusion: 50:22 Over the past two centuries, the relationship between Native American people and Mormonism has included friendly ties, displacement, battles, slavery, education placement programs, and official and unofficial discrimination.[1] Native American people (also called American Indians) were historically considered a special group by adherents of the Latter Day Saint movement (Mormons) since they were believed to be the descendants of the Lamanite people described in The Book of Mormon.[2]: 196 [3] There is no support from genetic studies and archaeology for the historicity of the Book of Mormon or Middle Eastern origins for any Native American peoples.[4][5][6] Today there are many Native American members of Mormon denominations as well as many people who are critical of Mormonism and its teachings and actions around Native American people.[7] History Under Joseph Smith The founder of Mormonism, Joseph Smith, was fascinated by Native Americans from an early age.[8]: 275 Scholars Lori Taylor and Peter Manseau believe religious teachings of then deceased Handsome Lake relayed through his nephew Red Jacket near Smith's town influenced the 16-year-old Smith.[9][10] Smith later stated that in 1823 a Native American angel visited him and told him about a record that contained an ancient history of Native Americans.[8]: 276 Smith said he translated this record from golden plates to The Book of Mormon. Smith stated in the 1842 Wentworth Letter to a Chicago newspaper editor that the book was "the history of ancient America ... from its first settlement by a colony that came from the Tower of Babel ... to the beginning of [400 CE] ... The remnant are the Indians that now inhabit this country."[11][12][13] The existence of the "red sons of Israel" (i.e. Native American) was used as evidence for the authenticity of this account.[8]: 277 Artist's depiction of Joseph Smith preaching to the Sac and Fox Indians who visited Nauvoo, Illinois, in 1841 Adherents saw Native Americans as part of God's chosen people and they believed that preaching to them was part of the gathering of Israel which will precede the millennium.[17] The church's long history with Native Americans is tied to their beliefs about The Book of Mormon.[8]: 277, 279 According to sociologist Marcie Goodman, historically Latter Day Saints held paternalistic beliefs about Native Americans needing help.[15] Outreach to Native Americans became the first mission of Smith's newly organized Church of Christ, as the purpose of The Book of Mormon was to recover the lost remnant of the ancient children of Israel (e.g. Native Americans).[20] Smith sent prominent members Oliver Cowdery, Parley Pratt, Peter Whitmer, Jr., and Ziba Peterson to a "Lamanite Mission" only six months after organizing the church.[18]: 122 Though they did not have any converts and reception was lukewarm among the Seneca, Wyandot, and Shawnee people, they were well received by the Delaware people because The Book of Mormon advocated for a divine destiny for Native Americans and a divine right to their territory in the American "promised land".[19]: 96–100 [2]: 196, 200 During the 1840s, Smith sent missionaries to the Sioux (Dakota), Potawatomi (Bodéwadmi), Stockbridge (Mahican) people in Wisconsin and Canada. Additionally, representatives from the Sauk (Asakiwaki) and Fox (Meskwaki) people met with Smith at the Latter Day Saint headquarters in Nauvoo, Illinois.[21][22]: 492 Smith was quoted in a Nauvoo Council of Fifty meeting as stating "If the Lamanites won't hearken to our council, they shall be oppressed & killed until they will do it."[23][24] Counselor Orson Spencer stated subsequently that "The gospel to [Native Americans] is, they have been killed and scattered in consequence of their rejecting the everlasting Priesthood, and if they will return to the Priesthood and hearken to council, they shall have council enough, that shall save both them and us."[23][24] Later, Potawatomi leaders asked the Mormons to join them in an alliance with some other tribes, but Smith declined.[21] The governor of Iowa John Chambers was wary of these meetings which were reported to him by interpreter Hitchcock, as Chambers believed Smith was "an exceedingly vain and vindictive fellow" who might use an alliance with Potowatomi people to start a conflict to seek revenge against Missouri.[22]: 500–501 Under Brigham Young See also: Native Americans in Utah § Mormon Pioneers, and Mormon settlement techniques of the Salt Lake Valley After Smith's death and six months of a succession crisis, Brigham Young became leader of the majority of Smith's followers and the largest denomination in the Latter Day Saint movement, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS Church). Young discussed an alliance with some Native American nations with other top leaders but these efforts were abandoned in 1846 as Young's followers were preparing to migrate west.[21] According to former Church Historian and emeritus church Seventy Marlin Jensen, before Mormon colonization of the region there were about 20,000 Native American people in the Great Basin.[28] These included the Shoshone, Goshute, Ute, Paiute, and Navajo nations.[26][27]: 273 The settlers initially had some peaceful relations, but because resources were scarce in the desert, hostilities broke out.[26] As tens of thousands of LDS colonizers arrived and took over the land, and resources Native Americans had used for thousands of years diminished, native nations felt they had to resist for their survival.[25]: 21—23 [26] Relationship during Utah War Mormon relations with Native Americans were a significant factor in President Buchanan's decision to order the U.S. army to Utah, beginning a conflict that would later be called the Utah War.[29] Brigham Young and other church leaders taught that by accepting baptism and intermarriage with Mormons, Native Americans would fulfill a Book of Mormon prophecy that Lamanites would return to the House of Israel.[29] While it is no longer a core tenant of the Latter-day faith, at the time leaders taught that "the time had arrived when all the wicked should be destroyed from the face of the earth, and that the Indians would be the principal means by which this object should be accomplished."[29]: 76 Gaining Native American allies was a key part of Brigham Young's strategy to maintain independence from the United States.[29] In 1855 Brigham Young called 160 missionaries to preach to North American Native Americans from the west coast to the Mississippi; over the next three years at least three hundred missionaries would construct mission forts among tribes along major immigration trails.[29] In a report to the commissioner of Indian affairs, Garland Hurt wrote, "There is perhaps not a tribe on the continent that will not be visited... [to create] a distinction in the minds of the Indian tribes of this Territory between the Mormons and the people of the United States."[29]: 76 Reports from Indian agents across the country confirmed Hurt's claims.[29] Furthermore, in the spring of 1857, Brigham Young violated federal law when he travelled outside of his jurisdiction as Utah's Superintendent of Indian affairs to meet with Native American leaders throughout the Oregon territory and give them gifts, which he later falsely reported were presents he gave to Indians in Utah.[29] Federal law made it a crime to alienate Indians from the United States government, and the president had the power to use military force to stop anyone attempting to do so.[29] As continuing problems from the territory became harder for US politicians to ignore, Stephen A. Douglas stated that "The Mormon Government, with Brigham Young at its head, is now forming alliance with Indian tribes in Utah and adjoining territories--stimulating the Indians to acts of hostility."[29]: 142 Despite public denials of this accusation, Nauvoo Legion commanders were concurrently ordered to warn Native Americans that they must unite together with the Mormons against the US government or be killed off by Americans separately.[29] As Brigham Young cut off emigration routes between the Eastern states and California (blaming Native American violence for the closures) President Buchanan ordered the US army to escort a new governor and Superintendent of Indian Affairs to the Utah territory.[29] Ultimately, while Mormons were able to establish some alliances with Southern Paiute tribes, the refusal of tribes in the north of Utah disrupted one of Brigham Young's primary war strategies.[29] In particular, Young was taken by surprise by the Bannock and Shoshone attack on the Mormon missionary Fort Lemhi for the benefit of the US troops.[29][30] This miscalculation of Native American alliances led him to begin overtures of peace with the US army.[29][30] Young's policies after the Utah War By 1860 the population of Mormon migrants in Utah had grown to 40,000 and within another ten years that number had doubled to 86,000.[27]: 266 By 1890 Native Americans made up only 1.6% of Utah's population.[31]: 112 Over a century later in 2010 that number had remained about the same at 1.3%.[32] Within 50 years of Mormon settlement the population of Utah's Native Americans had gone from 20,000 to under 2,700, a large decline of 86%.[27]: 273 Young stated, "towards so degraded and ignorant a race of people, it was manifestly more economical and less expensive, to feed and clothe, than fight them."[36] Of the monumental LDS colonization of the Intermountain West LDS leader Jensen stated, "Regardless of how one views the equities of Indian-Mormon relations in those times, the end result was that the land and cultural birthright Indians once possessed in the Great Basin were taken from them. ... [T]he least we can do from a distance of 160 years, is to acknowledge and appreciate the monumental loss this represents on the part of Utah's Indians. That loss and its 160-year aftermath are the rest of the story."[37][25]: 24 Young taught that cursed racial lineages were in a three-tiered classification of redemption with Lamanites (Native Americans) on top, Jewish people in the middle, and Cain's descendants (Black people) on the bottom.[2]: 205–206 This corresponded to the time when they would each receive the gospel, with Native Americans in the foreseeable future, Jewish people after they were gathered at the Second Coming of Jesus Christ, and Black people in the afterlife during the resurrection.[2]: 205–206 Young sent Jacob Hamblin as a leader for several missionary efforts among Great Basin Native Americans resulting in important Hopi conversion of Chief Tuba.[38] In the 1890s, James Mooney of the Smithsonian Institution of the Bureau of American Ethnology, and Missouri military commander Nelson Miles, placed some blame on Mormon settlers for the events that precipitated the Wounded Knee Massacre.[39]: 94, 97 Some later scholars perpetuated these ideas, however, historical evidence does not support them.[39]: 89 Chief Sagwitch and spouse Beawoachee, circa 1875 Though, nearly killed by US soldiers in the 1863 Bear River Massacre, Chief Sagwitch became a notable ally of Young and church member by 1873. 100 of his people were also baptized into the LDS Church, and they settled and farmed in Washakie, Utah. They also contributed large amounts of labor towards the building of the Logan Utah Temple in the 1870s and 80s.[40]: xiv, 174 Sagwitch's grandson Moroni became the first Native American bishop in the LDS Church.[40]: xiv 20th Century During the century between 1835 and 1947 the official LDS hymnbook had lyrics discussing Native Americans which included the following statements: "And so our race has dwindled/ To idle Indian hearts ... And all your captive brothers/ From every clime shall come/ And quit their savage customs", "Great spirit listen to the Red Man's wail! ... Not many moons shall pass away before/ the curse of darkness from your skins shall flee".[42] In 1975 George P. Lee became the first Native American LDS general authority, though he was excommunicated in 1989, and later pleaded guilty in 1994 to having groped a young girl.[43] By 1977 the LDS Church stated that there were almost 45,000 Native American members in the US and Canada (a number larger than any other Christian denomination except the Roman Catholic Church).[44] In the latter half of the 20th century, the LDS Church sold lands that had served as settlements for Native American church members to private interests, as at Washakie, and the Natives were forced to move to other reservations or into nearby towns.[45] Spencer Kimball was an influential leader in church relations with Native Americans. Beginning in 1945 then apostle Spencer Kimball was assigned to be over church relations with Native Americans, and he would go on to become president of the church and was very influential in church actions and teachings around Native Americans for four decades until his death in 1985.[46]: 237 [47] Twentieth century teachings connecting modern Native Americans and Lamanites reached their height under the presidency of Spencer W. Kimball (1973 –1985),[48]: 159 then declined, but did not disappear.[49]: 157–159 For example in 1967, then apostle (later church president) Kimball stated that Native Americans were descendants of Middle Eastern settlers who traveled over the ocean, and were "not Orientals" of East Asian origin,[50] further quoting a previous First Presidency proclamation which said God, "has revealed the origin and the records of the aboriginal tribes of America, and their future destiny.-And we know it."[51] Kimball definitively stated in 1971, "The term Lamanite includes all Indians and Indian mixtures, such as the Polynesians ...." and, "the Lamanites number about sixty million; they are in all of the states of America from Tierra del Fuego all the way up to Point Barrows, and they are in nearly all the islands of the sea from Hawaii south to southern New Zealand."[49]: 159 [52] The 1981 edition of the Book of Mormon said Lamanites "are the principal ancestors of the American Indians".[48]: 159 No evidence of the large civilizations or battles described in The Book of Mormon have been found by anthropologists and archaeologists, and DNA studies of Native Americans show that they came from Asia during the latest ice age, and not from the Middle East.[7][53][54] 21st Century The LDS Church altered statements after 2007 to say that Lamanites are "among the ancestors" rather than the "principal ancestors" of Native Americans.[55][7] Church manuals state that Christopher Columbus was inspired by God to sail to the Americas, and The Book of Mormon teaches that because the Lamanites sinned against God, they lost their lands and became "scattered and smitten". LDS-raised and ethnically native Alaskan Sarah Newcomb stated that this framing excuses the genocide of Native Americans during the post-Columbus European colonization of the Americas.[7] In 2021 an offered $2 million donation by the church to the First Americans Museum for a Native American family history center was declined.[56] Native American enslavement See also: Mormonism and slavery Kahpeputz was a slave in Brigham Young's household for over a decade.[57][58] The LDS Church's stance towards slavery alternated several times in its history, from one of neutrality, to anti-slavery, to pro-slavery. Smith had at times advocated both for and against slavery, eventually coming to take an anti-slavery stance later in his life. According to historian Andres Resendez, one of Smith's successors Brigham Young and other LDS leaders in Utah Territory leaders "did not so much want to do away with Indian slavery as to use it for their own ends."[27]: 272 Young officially legalized Native American slavery in the Utah Territory in 1852 with each purchased Native American person allowed to be held up to twenty years in indentured servitude.[27]: 272 [59] Children between seven and sixteen years old were supposed to be sent to school three months of the year, but were otherwise put to work.[27]: 273 Soon after Mormons colonized the Salt Lake Valley in 1847 child slaves became a vital source of their labor, and were exchanged as gifts.[59] Within a decade of settling the Salt Lake Valley over 400 Native American children were purchased and lived in Mormon homes.[59] In 1849 a posse of around 100 LDS men in southern Utah chased and killed twenty-five Native American men in retaliation for some cattle raids, and their women and children were taken as slaves.[27]: 274 Leader Brigham Young advocated buying children held by Native Americans and Mexican traders as slaves, and encouraged Latter-day Saints to educate and acculturate the children as if they were their own.[60][61][59] However, despite the requirement to educate the Native American indentured servants, the majority had received no formal education according to an 1860 census.[16]: 279 Young's spouse owned a Native American slave Kahpeputz. At age seven she was kidnapped from her Bannock family and tortured, and later purchased by Brigham Young's brother-in-law and gifted to one of Young's wives and renamed Sally.[58] She was a servant in the Young household for over a decade working long hours with the rest of the servants and was not taught to read or write.[57] While considering appropriations for Utah Territory, Representative Justin Smith Morrill criticized the LDS Church for its laws on Indian slavery. He said that the laws were unconcerned about the way the Indian slaves were captured, noting that the only requirement was that the Indian be possessed by a White person through purchase or otherwise. He said that Utah was the only American government to enslave Indians, and said that state-sanctioned slavery "is a dreg placed at the bottom of the cup by Utah alone".[62] The Republicans' abhorrence of slavery in Utah delayed Utah's entrance as a state into the Union. In 1857, Representative Justin Smith Morrill estimated that there were 400 Indian slaves in Utah.[62] Richard Kitchen has identified at least 400 Indian slaves taken into Mormon homes, but estimates even more went unrecorded because of the high mortality rate of Indian slaves. Many of them tried to escape.[27]: 273, 274 Slavery in Utah ended in 1862 when the United States Congress abolished it nationwide. In a 2020 general conference address church apostle Quentin Cook said of early church history, "Many [non-Mormon] Missourians considered Native Americans a relentless enemy and wanted them removed from the land. In addition, many of the Missouri settlers were slave owners and felt threatened by those who were opposed to slavery. In contrast, our doctrine respected the Native Americans, and our desire was to teach them the gospel of Jesus Christ. With respect to slavery, our scriptures had made it clear that no man should be in bondage to another."[63] Violence See also: Mormonism and violence Battles See also: American Indian Wars § Great Basin Violence between Mormon adherents and Native Americans include the Black Hawk War, Ute Wars, Wakara's (Walker's) War, and Posey War. Ute and Paiute Native Americans involved in the 1923 Posey War in southeast Utah Massacres of Native American people by LDS adherents See also: List of Indian massacres in North America § 1830–1915 Timpanogos extermination order During the 1850 escalation to the Battle at Fort Utah, Brigham Young ordered his Deseret Territorial Militia to "go and kill" the Timpanogos people of Utah Valley, further stating, "We have no peace until the men [are] killed off—never treat the Indian as your equal". He clarified that the militia should "let the women and children live if they behave themselves."[64][65] Following this order was the "bloodiest week of Indian killing in Utah history."[66]: 54 By the end of the wintertime conflict over 100 Timpanogos Utes were killed by Young's forces, and 50 of their bodies were beheaded and their heads put on display for several weeks in Fort Utah as a warning to the 26 surviving Native American women and children prisoners from the conflict held there.[69] The prisoners were then distributed to LDS families to be used as slaves.[67]: 711 [70]: 76 Table of massacres Year (Date) Name Current location (state) Description Reported deaths 1849 (Mar 5) Battle Creek massacre Utah In response to some cattle being stolen, Governor Brigham Young sent members of the Mormon militia to "put a final end to their depredations". They were led to a band, where they attacked them, killing the men and taking the women and children as captives.[71] 4 (more by some accounts) 1850 (Feb 8) Provo River Massacre Utah Governor Brigham Young issued a partial extermination order of the Timpanogos who lived in Utah Valley. In the north, the Timpanogos were fortified. However, in the south, the Mormon militia told them they were friendly before lining them up to execute them. Dozens of women and children were enslaved and taken to Salt Lake City, Utah, where many died.[72] 102 (& "many" taken captive) 1851 (Apr 23) Skull Valley massacre Utah In retaliation for the theft of horses near Tooele, Utah, Porter Rockwell and company took 30 uninvolved Utes camped nearby on Rush Lake as prisoners, and–after most escaped—executed the five remaining captives in nearby Skull Valley.[73][74]: 38–39 5 1853 (Oct 2) Nephi massacre Utah Eight uninvolved Goshute men were shot in retaliation for the previous days murder of four LDS people by unknown Ute people.[75][76] 8 1865 (Jul 18) The Squaw Fight/The Grass Valley Massacre Utah While searching for Antonga Black Hawk, the Mormon militia came upon a band of Ute Indians. Thinking they were part of Black Hawk's band, they attacked them. They killed 10 men and took the women and children captive. After the women and children tried to escape, the militia shot them too.[74]: 159–161 10 men + unknown women and children 1866 (Apr 21) Circleville Massacre Utah Mormon militiamen killed 16 Paiute men and women at Circleville, Utah. 6 men were shot, allegedly while trying to escape. The others (3 men and 7 women) had their throats cut. 4 small children were spared.[77] 16 Massacres of LDS adherents by Native American people See also: List of Indian massacres in North America § 1830–1915 Year (Date) Name Current location (state) Description Reported deaths 1853 (Oct 1) Fountain Green Massacre Utah Four LDS travelers were killed by Ute people.[75] 4 1858 (Jun 4) Salt Creek Canyon massacre Utah Four Danish immigrants traveling by wagon to Sanpete County, Utah were killed by unknown Native Americans.[78] 4 Mountain Meadows Massacre Main article: Mountain Meadows Massacre In 1857 LDS militiamen dressed up as Native Americans and recruited a smaller party of Southern Paiutes for a five-day siege on a wagon train of White pioneers travelling from Arkansas to California through Utah. The disguises were an attempt to shift blame for the aggression from White Mormon people onto the local Native Americans, and for many years after, the mass murder which became known as the Mountain Meadows Massacre was blamed on Paiute Indians.[79] During the militia's first assault on the wagon train, the emigrants fought back, and a five-day siege ensued. Eventually, fear spread among the militia's leaders that some emigrants had caught sight of the White men, likely discerning the actual identity of a majority of the attackers. As a result, militia commander William H. Dame ordered his forces to kill all the adults. 120 men and women, and all their children over the age of seven were slaughtered and their bodies left unburied.[80] The massacre almost pushed the US government into the Utah War with the LDS Church.[80] Bear River Massacre Main article: Bear River Massacre In 1863 (Jan 29) Col. Patrick Connor led a United States Army regiment killing up to 280 Shoshone men, women and children near Preston, Idaho under the urging of Mormon residents of Cache Valley, Utah after the killing of several cattle by Shoshoni men from Wyoming. The people of this camp had not been involved in the cattle killing. Refugees from this massacre moved into Box Elder County where they converted to Mormonism and eventually settled on church-owned property at Washakie, Utah.[81][82] Indian Placement Program Main article: Indian Placement Program The Indian Placement Program (also called the Indian Student Placement Program and the Lamanite Placement Program) was operated by the LDS Church in the United States, officially operating from 1954 and virtually closed by 1996. It had its peak during the 1960s and 1970s.[83] Native American students who were baptized members of the LDS Church were placed in foster homes of LDS members during the school year. They attended majority-White public schools, rather than the Indian boarding schools or local schools on the reservations. This was in line with the Indian Relocation Act of 1956. An LDS author wrote in 1979 that in southeast Idaho Native Americans from reservations were often treated with disdain by LDS and non-LDS White people.[14]: 378 [84] The program was developed according to LDS theology, whereby conversion and assimilation to Mormonism could help Native Americans.[15] An estimated 50,000 Native American children went through the program.[85][3] The foster placement was intended to help develop leadership among Native Americans and assimilate them into majority-American culture. The cost of care was borne by the foster parents, and financially stable families were selected by the church. Most of these placements took place on the Navajo Nation, with a peak participation of 5,000 students in 1972. The program decreased in size after the 1970s, due to criticism, changing mores among Native Americans, and restriction of the program to high school students as schools improved on reservations. In the 70s and 80s more Native Americans attended the church's Brigham Young University than any other major US institution of higher learning.[7] Many of the students and families praised the program; others criticized it and the LDS Church for assimilationist policies weakening the Native Americans' ties to their own cultures.[7] In the spring of 2015, four plaintiffs (now referred to as the "Doe Defendants") filed suit in the Window Rock District of the Navajo Nation Tribal Court, alleging they had been sexually abused for years while in the foster program, roughly from the years 1965 to 1983, and the LDS Church did not adequately protect them.[86] The LDS church filed suit in federal district court in Salt Lake City, alleging that the Tribal Court did not have jurisdiction and seeking an injunction "to stay the proceedings from moving forward under tribal jurisdiction."[86] Federal district court judge Robert Shelby denied the church's motion to dismiss and also ruled that it first had to "exhaust all remedies" in Tribal Court.[86] Teachings on Native American skin color See also: Mormon teachings on skin color Shivwits Band of Paiute people being baptized into the LDS Church by White missionaries in 1875 Several church leaders have stated that The Book of Mormon teaches that Native Americans have dark skin (or the "curse of redness") because their ancestors (the Lamanites) were cursed by God, but if Native Americans follow church teachings, their dark skin will be removed.[87][2]: 205, 207 Not far into the narrative of The Book of Mormon God marks Lamanites (the presumed ancestors of Native Americans) with dark skin because of their iniquity, an act similar to the Bible's Curse of Cain which later some Protestants interpreted as the beginning of the Black race.[18]: 97–98 The Book of Mormon passage states, "[God] had caused the cursing to come upon [the Lamanites] ... because of their iniquity ... wherefore, as they were White, and exceeding fair and delightsome, that they might not be enticing unto my people [the Nephites] the Lord God did cause a skin of blackness to come upon them."[44][88] During the century between 1835 and 1947 the official LDS hymnbook had lyrics discussing a lightening of Native American skin color stating, "Great spirit listen to the Red Man's wail! ... Not many moons shall pass away before/ the curse of darkness from your skins shall flee".[89] They taught that in the afterlife's highest degree of heaven Native American's skin would become "white in eternity" like everyone else.[90][91] They often equated Whiteness with righteousness, and taught that originally God made his children White in his own image.[92]: 231 [93][91] A 1959 report by the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights found that most Utah Mormons believed "by righteous living, the dark-skinned races may again become 'white and delightsome'."[94] Conversely, the church also taught that White apostates would have their skins darkened when they abandoned the faith.[95] In 1953, President of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles Joseph Fielding Smith stated, "After the people again forgot the Lord ... the dark skin returned. When the Lamanites fully repent and sincerely receive the gospel, the Lord has promised to remove the dark skin.... Perhaps there are some Lamanites today who are losing the dark pigment. Many of the members of the Church among the Catawba Indians of the South could readily pass as of the White race; also in other parts of the South."[96][97] Additionally, in a 1960 LDS Church General Conference, apostle Spencer Kimball suggested that the skin of Latter-day Saint Native American was gradually turning lighter.[98] Mormons believed that through intermarriage, the skin color of Native Americans could be restored to a "white and delightsome" state.[99][100]: 64 Navajo general authority George Lee stated that he had seen some Native American members of the church upset over these teachings and that they did not want their skin color changed as they liked being brown, and so he generally avoided discussing the topic. Lee interpreted the teachings to mean everyone's skin would be changed to a dazzling white in the celestial kingdom.[44] Kimball, however, suggested that the skin lightening was a result of the care, feeding, and education given to Native American children in the home placement program.[44] In 1981, church leaders changed a scriptural verse about Lamanites in The Book of Mormon from stating "they shall be a white and delightsome people" to stating "a pure and delightsome people".[41]: 71 [101] Thirty-five years later in 2016, the LDS Church made changes to its online version of The Book of Mormon in which phrases on the Lamanite's "skin of blackness" and them being a "dark, loathsome, and filthy" people were altered.[102][103] In 2020 controversy over the topic was ignited again when the LDS church's recently printed manuals stated that the dark skin was a sign of the curse and the Lord placed the dark skin upon the Lamanites to keep the Nephites from having children with them.[104] In recent decades, the LDS Church has condemned racism and increased its proselytization efforts and outreach in Native American communities, but it still faces accusations of perpetuating implicit racism by not acknowledging or apologizing for its prior discriminatory practices and beliefs. A 2023 survey of over 1,000 former church members in the Mormon corridor found race issues in the church to be one of the top three reported reasons why they had disaffiliated.[105] Marriages between Native Americans and White Latter Day Saints See also: Interracial marriage and the LDS Church Jeanette Smith Dudley Leavitt Native American Jeanette Smith married LDS, European American Dudley Leavitt in 1860. In the past, LDS Church leaders have consistently opposed marriages between members of different ethnicities, but today, interracial marriage is no longer considered a sin. Early Mormon leaders made an exception to the interracial marriage teachings by allowing White LDS men to marry Native American women because Native Americans were viewed as being descended from the Israelites; however, under Young, leaders did not sanction White LDS women marrying Native American men.[100]: 64 [99] In 1890 Native Americans made up only 1.6% of Utah's population.[31]: 112 In the 1930s many states had laws banning Native Americans from marrying White people, though, Utah did not.[31]: 106 The 1831 transcript of a revelation by Joseph Smith approving marriages between church members and Native Americans, stating "For it is my will, that in time, ye should take unto you wives of the Lamanites and Nephites, that their posterity may become white, delightsome and Just, for even now their females are more virtuous than the gentiles." On July 17, 1831, Smith said that he received a revelation in which God wanted several early elders of the church to eventually marry Native American women in a polygamous relationship so that their posterity may become "white, delightsome, and just".[106][107] Though Smith's successor Young believed that Native American peoples were "degraded", and "fallen in every respect, in habits, custom, flesh, spirit, blood, desire",[108]: 213 he also allowed Mormon men to marry Native American women as part of a process that would make their people White and delightsome and restore them to their "pristine beauty" within a few generations.[111] Many church leaders had different views on these unions, however, and they were rare, and those in these marriages were looked down upon by many LDS community members.[112]: 33 [27]: 276 Native American men were prohibited from marrying White women in Mormon communities.[99] Though, he would later oppose the marriage of Native American men to White LDS women, Young performed the first recorded sealing ceremony between any "Lamanite" and White member in October 1845 when an Oneida man Lewis Dana and Mary Gont were sealed in the Nauvoo Temple.[16]: 188 Though few in number, another notable example of a Native American man marrying an LDS woman at the time was the 1890 marriage of Ute violinist David Lemmon and Josephine Neilson in the St. George Utah Temple.[113] More common, however, was the experience of Tony Tillohash in the early 1900s who was rejected by the parents of a White LDS woman he proposed to, and was told to marry among his people.[27]: 276 [114]: 51 LDS couple Caroline Josephine Neilson and David Lemmon in Utah, circa mid-1920s There is evidence that Young may have married[58] his Bannock[115] servant[114]: 66 Kahpeputz (Sally) Young. Kahpeputz would later marry Ute chief Kanosh) in a temple,[110]: 195 [14]: 150 and they were both buried in their LDS temple robes, a custom for LDS members.[108]: 215–216, 348 By 1870 only about 30 Mormon men had Native American wives,[31]: 121 and few further interracial marriages with Native Americans occurred. Later Mormons believed that Native American skins would be lightened through some other method.[100]: 119 Under the presidency of Spencer W. Kimball, the church discouraged interracial marriages with Native Americans.[116] In 2013, the LDS Church disavowed previous teachings which stated that interracial marriage is a sin.[117][118] Other Latter Day Saint groups' teachings In 1920, what was then the Reorganized Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints (now called the Community of Christ), published a pamphlet titled Whence Came the Red Man which summarized The Book of Mormon stating, "two great camps ... began to quarrel bitterly among themselves. Part of them became the color of fine copper and the red brethren fought against the white."[119]: 65–66 https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Church_of_Jesus_Christ_of_Latter-day_Saints_and_the_Kingdom_of_God The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints and the Kingdom of God From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints and the Kingdom of God[1] is a Mormon fundamentalist church in the Latter Day Saint movement. The sect was founded by Frank Naylor and Ivan Nielsen, who split from the Centennial Park group, another fundamentalist church over issues with another prominent polygamous family. The church is estimated to have 200–300 members,[2] most of whom reside in the Salt Lake Valley. The group is also known as the Neilsen Naylor Group. The church holds weekly meetings alternating between Malad, Idaho and the Church-house in Bluffdale, Utah. Polygamist roots The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints and the Kingdom of God's claims of authority are based around the accounts of John Wickersham Woolley, Lorin Calvin Woolley, and others of a meeting in September 1886 between LDS Church President John Taylor, the Woolleys, and others.[2] Prior to the meeting, Taylor is said to have met with Jesus Christ and the deceased church founder Joseph Smith, and to have received a revelation commanding that plural marriage should not cease, but be kept alive by a group separate from the LDS Church. The following day, the Woolleys, as well as Taylor's counselor George Q. Cannon, and others, were said to have been set apart to keep "the principle" alive. Split from the Centennial Park group The Centennial Park group is a polygamist sect based in the Arizona Strip. This group is itself a split from the Fundamentalist Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints (FLDS Church). The Centennial Park group refers to itself as the "Second Ward" and refers to the FLDS Church as the "First Ward". When Alma A. Timpson became leader of the Second Ward in 1988, he appointed Frank Naylor as apostle and Ivan Nielsen as high priest and later as bishop. Naylor and Nielsen disagreed with Timpson's leadership and they split from the Second Ward in 1990[3] with Naylor as leader. Much of the rivalry was based between interactions between Timpson's sons and Neilsen and Naylor's families. The new church Naylor and Nielsen were able to gather a number of followers from both the Centennial Park group and the FLDS Church.[4] Most of the members of the new group migrated north to the Salt Lake Valley in Utah where they have built a meeting house.[4] They continue to practice polygamy as well as other fundamentalist doctrines such as the Adam–God doctrine.[2] The church has also formed a close relationship[5] with the Church of Jesus Christ (Original Doctrine) Inc.,[6] an FLDS Church-offshoot based in Bountiful, British Columbia. Endowment House: In 2008, they began offering an Endowment ritual. After careful consideration among the presidency, one of the homes owned by their leaders was renovated for use in giving Endowments. See also Factional breakdown: Mormon fundamentalist sects List of fundamentalist sects in the Latter Day Saint movement Big Love HBO series about a fictional independent polygamous Mormon fundamentalist family References "Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints and the Kingdom of God, The". utah.gov. Utah Division of Corporations and commercial Code: Business Search. Archived from the original on November 29, 2014. Retrieved 18 November 2014. Utah Attorney General’s Office and Arizona Attorney General's Office. The Primer, Helping Victims of Domestic Violence and Child Abuse in Polygamous Communities Archived 2013-01-27 at the Wayback Machine. Updated June 2006. Page 21. "A Chronology of Modern Polygamy". Polygamy: The Mormon Enigma. WindRiver Publishing, Inc. 2008. Retrieved June 4, 2010. Hales, Brian C (2009). "The Naylor Group (Salt Lake County)". mormonfundamentalism.com. Archived from the original on October 8, 2009. Retrieved June 4, 2010. Adams, Brooke; Nate Carlisle (January 8, 2009). "Arrested: Leaders of FLDS-linked Canadian polygamous sect". The Salt Lake Tribune. Bountiful, British Columbia: MediaNews Group. Retrieved June 4, 2010. "LDS Church wins, Canadian polygamist loses in fight for 'Mormon' name". Salt Lake Tribune. 14 January 2015. Retrieved 19 January 2015. Finally giving up the fight, Blackmore has agreed to change his group's corporate name to the "Church of Jesus Christ (Original Doctrine) Inc. Further reading Hales, Brian C. (2007). Modern Polygamy and Mormon Fundamentalism: The Generations After the Manifesto(Salt Lake City, Utah: Greg Kofford Books). Quinn, D. Michael "Plural Marriage and Mormon Fundamentalism", Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought 31(2) (Summer 1998). "The Primer" - Helping Victims of Domestic Violence and Child Abuse in Polygamous Communities. A joint report from the offices of the Attorneys General of Arizona and Utah. Van Wagoner, Richard S. (1999). Mormon Polygamy: A History. UK: Prometheus Books. ISBN 0-941214-79-6.91 views -

1830's Fashion Evolution -- What did they wear and when?

TThe Mormon ObserverOriginal Source: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iLn4qWGgA10 1830's fashion does not get enough love. Like, seriously. It's such a goofy, fun, adorable era for fashion, but it's kind of shoved right in there between two very beloved eras, the Regency period and the Victorian era. The 1830s, also known as the Romantic era, was a very transitional era for fashion, and it's fun to look at how things change and evolve throughout the period. So let's take a little deep dive into the styles of the 1830's! Check out my current 1830's project at this playlist: • Plaid 1830's Dress My 1830's Pinterest Board: / 1830s The Dames a la Mode Tumblr is a great resource for dated plates. Just change the year in the url, and it will turn up a few plates per year: https://damesalamode.tumblr.com/tagge... Want to learn about Regency fashion? Check out this video: • Regency Corsets, and How to Make Rege... Links My instagram: / ladyrebeccafashions Become a Patron! / ladyrebeccafashions Help support my channel on Ko-Fi: http://ko-fi.com/ladyrebeccafashions My Favorite Sewing Tools: https://www.amazon.com/shop/ladyrebec... What I use for filming: https://www.amazon.com/shop/ladyrebec... Business inquiries: [email protected] My PO Box: Lady Rebecca Fashions PO Box 695 Auburn, WA 98071 Amazon links are affiliate links. It really helps me out if you use them!47 views -

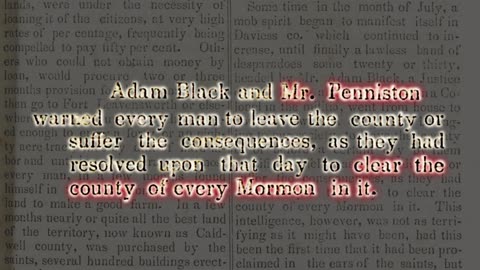

The Missouri Mormon War of 1838