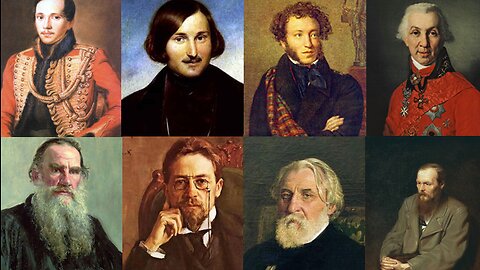

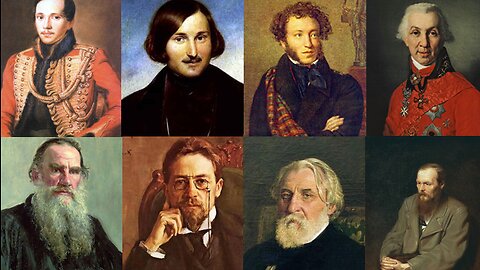

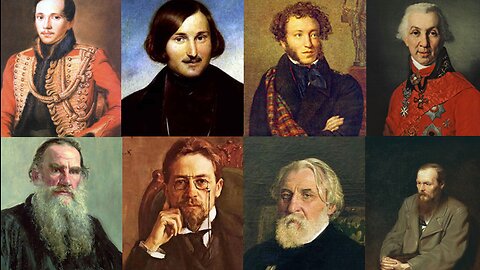

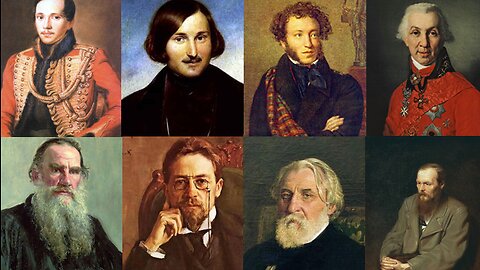

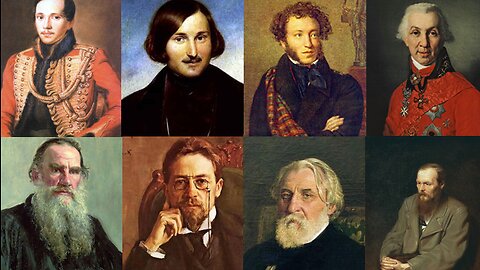

Classics of Russian Literature

36 videos

Updated 6 months ago

36 lectures, 30 minutes/lecture

Taught by Irwin Weil

Northwestern University

Ph.D., Harvard University

-

Classics of Russian Literature | Origins of Russian Literature (Lecture 1)

Adaneth - Arts & Literature36 lectures, 30 minutes/lecture Taught by Irwin Weil Northwestern University Ph.D., Harvard University Throughout the entire world, Russian culture - and most especially its 19th century literature - has acquired an enormous reputation. Like the heydays of other cultures - the Golden Age of Athens, the biblical period of the Hebrews, the Renaissance of the Italians, the Elizabethan period in England - the century of Tolstoy, Dostoevsky, Pushkin, and other great Russian writers seems, to many readers, like a great moral and spiritual compass, pointing the way toward deeper and wider understanding of what some call “the Russian soul,” but many others would call the soul of every human being. How did this culture come about, within the context of a huge continental country, perched on the cusp between European and Asiatic civilizations, taking part in all of them yet not becoming completely subject to or involved in any of them? What were the origins of this culture? How did it grow and exert its influence, first on its neighbors, then on countries and civilizations far from its borders? What influences did it feel from without, and how did it adapt and shape these influences for Russian ends? What were its inner sources of strength and understanding that allowed it to touch - and sometimes to clash with - these other cultures and still come out with something distinctively Russian? What wider implications does this process have for the entire human race? These 36 half-hour lectures delve into this extraordinary body of work under the guidance of Professor Irwin Weil of Northwestern University, an award-winning teacher at Northwestern University and a legend among educators in the United States and Russia. Professor Weil introduces you to such masterpieces as Tolstoy's War and Peace, Dostoevsky's Crime and Punishment, Pushkin's Eugene Onegin, Gogol's Dead Souls, Chekhov's The Seagull, Pasternak's Doctor Zhivago, and many other great novels, stories, plays, and poems by Russian authors. You will also investigate the origin of Russian literature itself, which traces to powerful epic poetry and beautiful renderings of the Bible into Slavic during the Middle Ages. The central core of the course covers the great golden age of Russian literature, a period in the 19th century when Russia's writers equaled or surpassed the achievements of the much older literary cultures of Western Europe. The age commenced with Pushkin, developed with the fantastic and grotesque tales of Gogol', and grew to full flower with Dostoevsky and Tolstoy - who at the time were considered in Europe to be lesser writers than their talented contemporary Turgenev. As the 20th century approached, Chekhov's exquisitely understated plays and stories symbolized the sunset of the golden age. Gorky straddled the next transformation, linking the turmoil preceding the Russian Revolution with the political oppression that affected all artists in the newly established Soviet Union from the 1920s on. You examine the brilliant revolutionary poet Maiakovsky; the novelist Sholokhov, who portrayed the revolution as a tragedy for the Cossack people; the satirist Zoshchenko, who used Soviet society as food for parody; and Pasternak, who produced beautiful poems and a single extraordinary novel. Your survey ends with Solzhenitsyn, who first exposed the reality of the Soviet forced labor camps and continued to speak prophetically until he reached what he considered enlightened new nationalism. Lecture 1: Russian literature had its national and spiritual origins in the territory around the ancient city of Kiev, which was the sometimes grudgingly accepted center of a number of settlements and city-states, a loose confederation called “Kievan Rus’.” From the 10th century A.D., its literature was deeply involved with both religion and politics. When Vladimir, prince of Kiev, in A.D. 988–989, sought a dynastic alliance by marrying the sister of the Byzantine emperor, he returned not only with a literate (and presumably beautiful) wife but also with many documents of the Eastern Orthodox Church. These documents, some of which we will examine, had been translated by a genius, St. Cyril, into the 9th-century language spoken by all Slavic peoples. This church literature bore a deeply religious feeling derived from the New Testament and rendered exquisitely by Cyril’s translations. The connections between Russian literature and politics and ideology started almost 1,000 years before the advent of the Soviet Union and its Marxist ideology. Suggested Reading: Samuel Hazard Cross and Olgerd P. Sherbowitz-Wetzor, eds., The Russian Primary Chronicle. Nicolas Riasanovsky, History of Russia.441 views 2 comments

Adaneth - Arts & Literature36 lectures, 30 minutes/lecture Taught by Irwin Weil Northwestern University Ph.D., Harvard University Throughout the entire world, Russian culture - and most especially its 19th century literature - has acquired an enormous reputation. Like the heydays of other cultures - the Golden Age of Athens, the biblical period of the Hebrews, the Renaissance of the Italians, the Elizabethan period in England - the century of Tolstoy, Dostoevsky, Pushkin, and other great Russian writers seems, to many readers, like a great moral and spiritual compass, pointing the way toward deeper and wider understanding of what some call “the Russian soul,” but many others would call the soul of every human being. How did this culture come about, within the context of a huge continental country, perched on the cusp between European and Asiatic civilizations, taking part in all of them yet not becoming completely subject to or involved in any of them? What were the origins of this culture? How did it grow and exert its influence, first on its neighbors, then on countries and civilizations far from its borders? What influences did it feel from without, and how did it adapt and shape these influences for Russian ends? What were its inner sources of strength and understanding that allowed it to touch - and sometimes to clash with - these other cultures and still come out with something distinctively Russian? What wider implications does this process have for the entire human race? These 36 half-hour lectures delve into this extraordinary body of work under the guidance of Professor Irwin Weil of Northwestern University, an award-winning teacher at Northwestern University and a legend among educators in the United States and Russia. Professor Weil introduces you to such masterpieces as Tolstoy's War and Peace, Dostoevsky's Crime and Punishment, Pushkin's Eugene Onegin, Gogol's Dead Souls, Chekhov's The Seagull, Pasternak's Doctor Zhivago, and many other great novels, stories, plays, and poems by Russian authors. You will also investigate the origin of Russian literature itself, which traces to powerful epic poetry and beautiful renderings of the Bible into Slavic during the Middle Ages. The central core of the course covers the great golden age of Russian literature, a period in the 19th century when Russia's writers equaled or surpassed the achievements of the much older literary cultures of Western Europe. The age commenced with Pushkin, developed with the fantastic and grotesque tales of Gogol', and grew to full flower with Dostoevsky and Tolstoy - who at the time were considered in Europe to be lesser writers than their talented contemporary Turgenev. As the 20th century approached, Chekhov's exquisitely understated plays and stories symbolized the sunset of the golden age. Gorky straddled the next transformation, linking the turmoil preceding the Russian Revolution with the political oppression that affected all artists in the newly established Soviet Union from the 1920s on. You examine the brilliant revolutionary poet Maiakovsky; the novelist Sholokhov, who portrayed the revolution as a tragedy for the Cossack people; the satirist Zoshchenko, who used Soviet society as food for parody; and Pasternak, who produced beautiful poems and a single extraordinary novel. Your survey ends with Solzhenitsyn, who first exposed the reality of the Soviet forced labor camps and continued to speak prophetically until he reached what he considered enlightened new nationalism. Lecture 1: Russian literature had its national and spiritual origins in the territory around the ancient city of Kiev, which was the sometimes grudgingly accepted center of a number of settlements and city-states, a loose confederation called “Kievan Rus’.” From the 10th century A.D., its literature was deeply involved with both religion and politics. When Vladimir, prince of Kiev, in A.D. 988–989, sought a dynastic alliance by marrying the sister of the Byzantine emperor, he returned not only with a literate (and presumably beautiful) wife but also with many documents of the Eastern Orthodox Church. These documents, some of which we will examine, had been translated by a genius, St. Cyril, into the 9th-century language spoken by all Slavic peoples. This church literature bore a deeply religious feeling derived from the New Testament and rendered exquisitely by Cyril’s translations. The connections between Russian literature and politics and ideology started almost 1,000 years before the advent of the Soviet Union and its Marxist ideology. Suggested Reading: Samuel Hazard Cross and Olgerd P. Sherbowitz-Wetzor, eds., The Russian Primary Chronicle. Nicolas Riasanovsky, History of Russia.441 views 2 comments -

Classics of Russian Literature | The Church and the Folk in Old Kiev (Lecture 2)

Adaneth - Arts & LiteratureLecture 2: When Prince Vladimir’s agents and allies tried to spread the new Christian beliefs and ceremonies among the people - mostly illiterate, but by no means stupid peasants, there arose a genuine and stubborn conflict: the old pre-Christian legends and gods versus the new ideas of salvation and grace through Jesus Christ and his powerful preaching. The result, which lasted for centuries, was called dvoeverie (two faiths, side by side). The new faith was literarily represented by St. Cyril’s magnificent translations. The old faith persisted in oral folklore of an equally powerful expression. By the 13th century, the political situation changed substantially, with the invasion of Eastern peoples—the Tatars—under their famous leader Genghis Khan, whose military strategy and technology were very advanced for their time. One of Russia’s most precious literary productions, an epic poem called “The Tale of Prince Igor,” deals with Kiev’s initial defeat at the hands of the Polovetsians, precursors of the Tatars. Suggested Reading: Robert Mann, trans., The Song of Prince Igor. Serge A. Zenkovsky, ed., Medieval Russia’s Epics, Chronicles, and Tales.161 views

Adaneth - Arts & LiteratureLecture 2: When Prince Vladimir’s agents and allies tried to spread the new Christian beliefs and ceremonies among the people - mostly illiterate, but by no means stupid peasants, there arose a genuine and stubborn conflict: the old pre-Christian legends and gods versus the new ideas of salvation and grace through Jesus Christ and his powerful preaching. The result, which lasted for centuries, was called dvoeverie (two faiths, side by side). The new faith was literarily represented by St. Cyril’s magnificent translations. The old faith persisted in oral folklore of an equally powerful expression. By the 13th century, the political situation changed substantially, with the invasion of Eastern peoples—the Tatars—under their famous leader Genghis Khan, whose military strategy and technology were very advanced for their time. One of Russia’s most precious literary productions, an epic poem called “The Tale of Prince Igor,” deals with Kiev’s initial defeat at the hands of the Polovetsians, precursors of the Tatars. Suggested Reading: Robert Mann, trans., The Song of Prince Igor. Serge A. Zenkovsky, ed., Medieval Russia’s Epics, Chronicles, and Tales.161 views -

Classics of Russian Literature | Aleksandr Sergeevich Pushkin, 1799–1837 (Lecture 3)

Adaneth - Arts & LiteratureLecture 3: We now take a great chronological leap from the 13th century to the last year of the 18th. In the midst of the splendiferous and powerful Russian Empire, with its ancient capital of Moscow and new capital of St. Petersburg, we see the career of a new genius, descended from an African brought to Russia by Peter the Great. This bright young fellow is brought up in a family whose members adore French literature. They read it to the boy on every possible occasion, and his extraordinary memory fixes it in place. They then enroll him in a remarkable school, the Lycée (again, a French name) with the brightest young aristocrats of Russia, under highly talented teachers. Neither his mischief nor his flair for writing deserted him after he left the Lycée, and he soon found himself banished from St. Petersburg and forced to spend time in the colorful area of Bessarabia, in the southwestern part of the Russian Empire. Suggested Reading: T. J. Binyon, Pushkin - A Biography.152 views 1 comment

Adaneth - Arts & LiteratureLecture 3: We now take a great chronological leap from the 13th century to the last year of the 18th. In the midst of the splendiferous and powerful Russian Empire, with its ancient capital of Moscow and new capital of St. Petersburg, we see the career of a new genius, descended from an African brought to Russia by Peter the Great. This bright young fellow is brought up in a family whose members adore French literature. They read it to the boy on every possible occasion, and his extraordinary memory fixes it in place. They then enroll him in a remarkable school, the Lycée (again, a French name) with the brightest young aristocrats of Russia, under highly talented teachers. Neither his mischief nor his flair for writing deserted him after he left the Lycée, and he soon found himself banished from St. Petersburg and forced to spend time in the colorful area of Bessarabia, in the southwestern part of the Russian Empire. Suggested Reading: T. J. Binyon, Pushkin - A Biography.152 views 1 comment -

Classics of Russian Literature | Exile, Rustic Seclusion, and Onegin (Lecture 4)

Adaneth - Arts & LiteratureLecture 4: In Odessa, a thriving port city on the Black Sea, Pushkin managed to irritate the local governor, who soon sent him packing back to his parents’ country estates in the north of Russia. During this time, he began a long work that would become Russia’s greatest poem. He called it a “novel in verse”: Eugene Onegin. Inspired partly by Byron’s Don Juan, it dealt with many different literary themes and became an endless source of inspiration for writers and composers who came after Pushkin. Its central plot involves the title character, who is a strange combination of sensitivity, intelligence, and perversity. He recognizes the unusually high human value of the central female figure, Tatiana Larina, but rejects the love she offers when she is a young woman in the country. Later, when he sees her as a grande dame in St. Petersburg, it is his turn to experience rejection. The poem also deals with dueling and the death of the poet, perhaps a foreboding of the author’s fate Suggested Reading and Listening: Aleksandr Pushkin, Eugene Onegin, translation by James E. Falen. Aleksandr Pushkin, Eugene Onegin—A Novel in Verse, translation and commentary by Vladimir Nabokov. Petr I. Tchaikovsky, Eugene Onegin, an opera based on the poem.133 views

Adaneth - Arts & LiteratureLecture 4: In Odessa, a thriving port city on the Black Sea, Pushkin managed to irritate the local governor, who soon sent him packing back to his parents’ country estates in the north of Russia. During this time, he began a long work that would become Russia’s greatest poem. He called it a “novel in verse”: Eugene Onegin. Inspired partly by Byron’s Don Juan, it dealt with many different literary themes and became an endless source of inspiration for writers and composers who came after Pushkin. Its central plot involves the title character, who is a strange combination of sensitivity, intelligence, and perversity. He recognizes the unusually high human value of the central female figure, Tatiana Larina, but rejects the love she offers when she is a young woman in the country. Later, when he sees her as a grande dame in St. Petersburg, it is his turn to experience rejection. The poem also deals with dueling and the death of the poet, perhaps a foreboding of the author’s fate Suggested Reading and Listening: Aleksandr Pushkin, Eugene Onegin, translation by James E. Falen. Aleksandr Pushkin, Eugene Onegin—A Novel in Verse, translation and commentary by Vladimir Nabokov. Petr I. Tchaikovsky, Eugene Onegin, an opera based on the poem.133 views -

Classics of Russian Literature | December’s Uprising and Two Poets Meet (Lecture 5)

Adaneth - Arts & LiteratureLecture 5: In 1825, a group of aristocrats attempted an uprising on a St. Petersburg square. Naively, given that they had no widespread support, they thought they could overthrow the tsarist regime and replace it with a republic. Among these would-be revolutionaries were many friends of Pushkin. After an interview with the new tsar, the poet managed to extricate himself from these associations. He then discovered the work of another great poet - William Shakespeare, whose works Pushkin read in French translation. He was particularly impressed by the plays written about the guilt-ridden Henry IV, and he decided to respond in Russian. The result was his tragedy Boris Godunov, concerning events surrounding Russia’s early-17th-century “Time of Troubles.” The tragedy involves a Russian tsar who made his way to the throne by means of a murder and suffered the pangs of conscience. Naturally, the play had considerable political resonance on the Russian scene, which had just witnessed an attempted regime change. The resonance of the play was made even more powerful two generations later, when one of the greatest Russian composers, Modest Mussorgsky, converted the tragedy into one of the world’s greatest operas, Boris Godunov. Suggested Reading and Listening: Modest Mussorgsky, Boris Godunov, an opera based on the play. Aleksandr Pushkin, Boris Godunov. Aleksandr Pushkin, The Poems, Prose, and Plays of Alexander Pushkin, edited by Avrahm Yarmolinsky. William Shakespeare, Richard II; Henry IV, Part One; Henry IV, Part Two; Henry V.177 views 6 comments

Adaneth - Arts & LiteratureLecture 5: In 1825, a group of aristocrats attempted an uprising on a St. Petersburg square. Naively, given that they had no widespread support, they thought they could overthrow the tsarist regime and replace it with a republic. Among these would-be revolutionaries were many friends of Pushkin. After an interview with the new tsar, the poet managed to extricate himself from these associations. He then discovered the work of another great poet - William Shakespeare, whose works Pushkin read in French translation. He was particularly impressed by the plays written about the guilt-ridden Henry IV, and he decided to respond in Russian. The result was his tragedy Boris Godunov, concerning events surrounding Russia’s early-17th-century “Time of Troubles.” The tragedy involves a Russian tsar who made his way to the throne by means of a murder and suffered the pangs of conscience. Naturally, the play had considerable political resonance on the Russian scene, which had just witnessed an attempted regime change. The resonance of the play was made even more powerful two generations later, when one of the greatest Russian composers, Modest Mussorgsky, converted the tragedy into one of the world’s greatest operas, Boris Godunov. Suggested Reading and Listening: Modest Mussorgsky, Boris Godunov, an opera based on the play. Aleksandr Pushkin, Boris Godunov. Aleksandr Pushkin, The Poems, Prose, and Plays of Alexander Pushkin, edited by Avrahm Yarmolinsky. William Shakespeare, Richard II; Henry IV, Part One; Henry IV, Part Two; Henry V.177 views 6 comments -

Classics of Russian Literature | A Poet Contrasts Talent versus Mediocrity (Lecture 6)

Adaneth - Arts & LiteratureLecture 6: Pushkin was well aware, perhaps even immodestly so, of his extraordinary gifts; he often contrasted and compared them with the talents of other artists. In his earlier writings, he turned to Mozart: a genius, like Pushkin, who was often able spontaneously, without extensive labors or revisions, to pour out his talent in written notes, producing marvelous melodies and rhythms. Antonio Salieri, by contrast, labored within all the rules of harmony. The result was a clash of temperaments, which led, as legend had it, to Salieri’s murder of Mozart, “for the good of music” no less! Pushkin’s short drama Mozart and Salieri echoes that legend, as does Peter Shaffer’s play and film Amadeus. Later in his career, Pushkin looked with admiration at the great Polish poet Adam Mickiewicz. The result was a brilliant novella, Egyptian Nights, in which a character, in many ways like Pushkin himself, was the lesser talent, looking on as the gifted foreign improviser worked his magic on the glitterati of St. Petersburg. Suggested Reading: Aleksandr Pushkin, Egyptian Nights. Aleksandr Pushkin, Mozart and Salieri. Aleksandr Pushkin, The Complete Prose Fiction, translation and commentary by Paul Debreczeny. Aleksandr Pushkin, The Poems, Prose, and Plays of Alexander Pushkin, edited by Avrahm Yarmolinsky. Peter Shaffer, Amadeus, a play and a film.144 views 3 comments

Adaneth - Arts & LiteratureLecture 6: Pushkin was well aware, perhaps even immodestly so, of his extraordinary gifts; he often contrasted and compared them with the talents of other artists. In his earlier writings, he turned to Mozart: a genius, like Pushkin, who was often able spontaneously, without extensive labors or revisions, to pour out his talent in written notes, producing marvelous melodies and rhythms. Antonio Salieri, by contrast, labored within all the rules of harmony. The result was a clash of temperaments, which led, as legend had it, to Salieri’s murder of Mozart, “for the good of music” no less! Pushkin’s short drama Mozart and Salieri echoes that legend, as does Peter Shaffer’s play and film Amadeus. Later in his career, Pushkin looked with admiration at the great Polish poet Adam Mickiewicz. The result was a brilliant novella, Egyptian Nights, in which a character, in many ways like Pushkin himself, was the lesser talent, looking on as the gifted foreign improviser worked his magic on the glitterati of St. Petersburg. Suggested Reading: Aleksandr Pushkin, Egyptian Nights. Aleksandr Pushkin, Mozart and Salieri. Aleksandr Pushkin, The Complete Prose Fiction, translation and commentary by Paul Debreczeny. Aleksandr Pushkin, The Poems, Prose, and Plays of Alexander Pushkin, edited by Avrahm Yarmolinsky. Peter Shaffer, Amadeus, a play and a film.144 views 3 comments -

Classics of Russian Literature | St. Petersburg Glorified and Death Embraced (Lecture 7)

Adaneth - Arts & LiteratureLecture 7: Pushkin was well aware that Russian greatness and power were built on the suffering and labor of tens of millions of serfs and lower-class, urban serving people. In his narrative poem The Bronze Horseman, he contrasts the most famous invocation to the beauty of St. Petersburg—known as well by Russians as we know Hamlet’s “To be or not to be”—with the misery of those who live and perish under the yoke of Russia’s imperial establishment. Later, not long before his death, he erects his own monument, “not touchable by human hands,” to be admired by countless future Russian generations. In 1837, Pushkin, who felt he had to live in Russian high society, perished from a blow brought about by the Byzantine turnings of that same society. A French officer serving in the Russian army, Georges d’Anthès, virtually stalked Pushkin’s beautiful wife, Natalia. Pushkin’s enraged reactions, and a nasty anonymous letter, led to a duel that ended with a bullet in the poet’s abdomen and a hideously painful deatha death that Russia mourns to this very day. Suggested Reading: John Bayley, Pushkin: A Comparative Commentary. Ilya Kutik, Writing as ExorcismThe Personal Codes of Pushkin, Lermontov, and Gogol. Aleksandr Pushkin, The Bronze Horseman in Pushkin Threefold, poems translated by Walter Arndt.151 views

Adaneth - Arts & LiteratureLecture 7: Pushkin was well aware that Russian greatness and power were built on the suffering and labor of tens of millions of serfs and lower-class, urban serving people. In his narrative poem The Bronze Horseman, he contrasts the most famous invocation to the beauty of St. Petersburg—known as well by Russians as we know Hamlet’s “To be or not to be”—with the misery of those who live and perish under the yoke of Russia’s imperial establishment. Later, not long before his death, he erects his own monument, “not touchable by human hands,” to be admired by countless future Russian generations. In 1837, Pushkin, who felt he had to live in Russian high society, perished from a blow brought about by the Byzantine turnings of that same society. A French officer serving in the Russian army, Georges d’Anthès, virtually stalked Pushkin’s beautiful wife, Natalia. Pushkin’s enraged reactions, and a nasty anonymous letter, led to a duel that ended with a bullet in the poet’s abdomen and a hideously painful deatha death that Russia mourns to this very day. Suggested Reading: John Bayley, Pushkin: A Comparative Commentary. Ilya Kutik, Writing as ExorcismThe Personal Codes of Pushkin, Lermontov, and Gogol. Aleksandr Pushkin, The Bronze Horseman in Pushkin Threefold, poems translated by Walter Arndt.151 views -

Classics of Russian Literature | Nikolai Vasil’evich Gogol’, 1809–1852 (Lecture 8)

Adaneth - Arts & LiteratureLecture 8: Partly contemporary with Pushkin came the first great master of Russian prose, a man with a long, prominent nose that he immortalized in literature. Born in Ukraine, brought up with the rich folklore and devilish tales of that rich western region of the tsar’s empire, Gogol’ came to the capital in 1828, the year of Tolstoy’s birth. After a short, spectacularly unsuccessful career as a teacher, in 1836, he wrote a play, The Inspector General, whose performances attracted enormous attention among Russian spectators and readers, not least of all from Tsar Nikolai I. The play’s off-center sense of humor, combined with its bitingly mordant presentation of Russian corruption and civic disorder, made an impression that has lasted for 180 years with undiminished strength. Five years after writing the play, Gogol’ wrote one of the greatest masterpieces of the European novella form - The Overcoat. This portrayal of the travails experienced by a low-ranking St. Petersburg copyist and bureaucrat, a sort of human typewriter, has captured the sympathies and imagination of countless generations. Suggested Reading: Nikolai Gogol’, The Inspector General. Nikolai Gogol’, The Nose, The Overcoat, Diary of a Madman and Other Stories, translated and with an introduction by Ronald Wilks. Vladimir Nabokov, Nikolai Gogol.133 views

Adaneth - Arts & LiteratureLecture 8: Partly contemporary with Pushkin came the first great master of Russian prose, a man with a long, prominent nose that he immortalized in literature. Born in Ukraine, brought up with the rich folklore and devilish tales of that rich western region of the tsar’s empire, Gogol’ came to the capital in 1828, the year of Tolstoy’s birth. After a short, spectacularly unsuccessful career as a teacher, in 1836, he wrote a play, The Inspector General, whose performances attracted enormous attention among Russian spectators and readers, not least of all from Tsar Nikolai I. The play’s off-center sense of humor, combined with its bitingly mordant presentation of Russian corruption and civic disorder, made an impression that has lasted for 180 years with undiminished strength. Five years after writing the play, Gogol’ wrote one of the greatest masterpieces of the European novella form - The Overcoat. This portrayal of the travails experienced by a low-ranking St. Petersburg copyist and bureaucrat, a sort of human typewriter, has captured the sympathies and imagination of countless generations. Suggested Reading: Nikolai Gogol’, The Inspector General. Nikolai Gogol’, The Nose, The Overcoat, Diary of a Madman and Other Stories, translated and with an introduction by Ronald Wilks. Vladimir Nabokov, Nikolai Gogol.133 views -

Classics of Russian Literature | Russian Grotesque - Overcoats to Dead Souls (Lecture 9)

Adaneth - Arts & LiteratureLecture 9: Gogol’ was a tremendously restless person. Right after his success as a playwright, he set off for Western Europe, where his memories of rural Russia, filtered through his half-crazy imagination, produced an unforgettable series of grotesque and comic characters under the deceptive title of Dead Souls. Despite its morbid-sounding title, the novel gives a fascinating picture of a Russian plut (“rogue”), Chichikov. The very sibilant repetition in the name tells a great deal. In his rickety yet mighty troika, Chichikov slithers his way through the Russian provincial gentry, with a wondrously crooked plan, more than worthy of any world-class shyster. Later, Gogol’ tried to bring his rogue to virtue, with a lack of success that was clearly predictable: Paradise was not for this inveterate denizen of hell. Gogol’ did manage to irritate mightily his erstwhile friends and readers. A short time after receiving a missive from the great critic Belinsky, a letter that would have torn the hide off a hog, Gogol’ died with leeches hanging from his magnificent nose. Suggested Reading: Nikolai Gogol’, Dead Souls (a novel called a “poem”), with commentary at the end of the Norton edition. Francis B. Randall, Vissarion Belinsky.106 views

Adaneth - Arts & LiteratureLecture 9: Gogol’ was a tremendously restless person. Right after his success as a playwright, he set off for Western Europe, where his memories of rural Russia, filtered through his half-crazy imagination, produced an unforgettable series of grotesque and comic characters under the deceptive title of Dead Souls. Despite its morbid-sounding title, the novel gives a fascinating picture of a Russian plut (“rogue”), Chichikov. The very sibilant repetition in the name tells a great deal. In his rickety yet mighty troika, Chichikov slithers his way through the Russian provincial gentry, with a wondrously crooked plan, more than worthy of any world-class shyster. Later, Gogol’ tried to bring his rogue to virtue, with a lack of success that was clearly predictable: Paradise was not for this inveterate denizen of hell. Gogol’ did manage to irritate mightily his erstwhile friends and readers. A short time after receiving a missive from the great critic Belinsky, a letter that would have torn the hide off a hog, Gogol’ died with leeches hanging from his magnificent nose. Suggested Reading: Nikolai Gogol’, Dead Souls (a novel called a “poem”), with commentary at the end of the Norton edition. Francis B. Randall, Vissarion Belinsky.106 views -

Classics of Russian Literature | Fedor Mikhailovich Dostoevsky, 1821–1881 (Lecture 10)

Adaneth - Arts & LiteratureLecture 10: There is probably no writer since the Renaissance who has made a deeper impression on contemporary imagination and creativity than Dostoevsky, with the possible exception of his great contemporary, Tolstoy. (Let it only be said that it was Dostoevsky who forced the creator of this lecture series, at the age of 19, to learn the magnificent Russian language.) Dostoevsky was the son of a military Russian doctor in Moscow. He grew up in the city, and he did not partake of the great rural culture of Russia. Educated as an engineer but desperately in love with French and Russian literature, he wrote an epistolary novel, Poor Folk, in 1844, which he submitted to a prestigious journal. Its famous editor, Nekrasov, gave it to Belinsky (shades of Gogol’), who only grudgingly agreed to read the work of some nerdy engineer. Belinsky became totally engrossed in its artistry, swallowed the work whole, went to Dostoevsky’s apartment at 4:00 in the morning, embraced him, and declared the young man the future genius of Russia. Dostoevsky later wrote: “That was one of the rare moments in my life when I was truly happy.” The novel itself concerned not only the difficult life of Russian poor people but also many of the themes that Dostoevsky later elaborated. Suggested Reading: Fedor Dostoevsky, Poor Folk. Konstantin Mochulsky, Dostoevsky: His Life and Work.169 views

Adaneth - Arts & LiteratureLecture 10: There is probably no writer since the Renaissance who has made a deeper impression on contemporary imagination and creativity than Dostoevsky, with the possible exception of his great contemporary, Tolstoy. (Let it only be said that it was Dostoevsky who forced the creator of this lecture series, at the age of 19, to learn the magnificent Russian language.) Dostoevsky was the son of a military Russian doctor in Moscow. He grew up in the city, and he did not partake of the great rural culture of Russia. Educated as an engineer but desperately in love with French and Russian literature, he wrote an epistolary novel, Poor Folk, in 1844, which he submitted to a prestigious journal. Its famous editor, Nekrasov, gave it to Belinsky (shades of Gogol’), who only grudgingly agreed to read the work of some nerdy engineer. Belinsky became totally engrossed in its artistry, swallowed the work whole, went to Dostoevsky’s apartment at 4:00 in the morning, embraced him, and declared the young man the future genius of Russia. Dostoevsky later wrote: “That was one of the rare moments in my life when I was truly happy.” The novel itself concerned not only the difficult life of Russian poor people but also many of the themes that Dostoevsky later elaborated. Suggested Reading: Fedor Dostoevsky, Poor Folk. Konstantin Mochulsky, Dostoevsky: His Life and Work.169 views