-

The Murder of Erin Valenti, age 33, October 7, 2019.

Juxtaposition1Long Train Runnin' (the real-life story of Juxtaposition): https://juxtaposition1.substack.com/p/long-train-runnin-the-real-life-story https://juxtaposition1.substack.com/463 views 1 comment

Juxtaposition1Long Train Runnin' (the real-life story of Juxtaposition): https://juxtaposition1.substack.com/p/long-train-runnin-the-real-life-story https://juxtaposition1.substack.com/463 views 1 comment -

JFK, MLK, RFK, Zodiac, Tate-LaBianca, Kato Kaelin, Lou Brown, Vatican Bank

Juxtaposition1Long Train Runnin' (the real-life story of Juxtaposition): https://juxtaposition1.substack.com/p/long-train-runnin-the-real-life-story https://juxtaposition1.substack.com/485 views 1 comment

Juxtaposition1Long Train Runnin' (the real-life story of Juxtaposition): https://juxtaposition1.substack.com/p/long-train-runnin-the-real-life-story https://juxtaposition1.substack.com/485 views 1 comment -

Project Miranda was a NATO Gladio snuff film operation

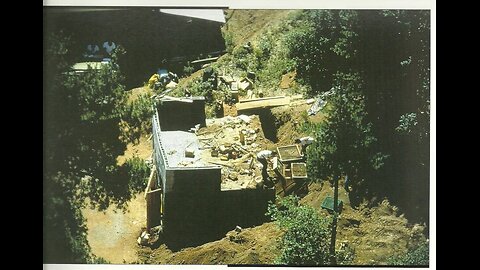

Juxtaposition1A Caste System prevails in all Hunger Game Districts worldwide. Scions (BANKERS, Landowner, Port Authorities, Maritime Law Courts) The Nobles, Judges, Chancellors, Popes, Cardinals, Bishops, Priests, CEOs) A Working Class The profane peasants Project Miranda, (Leonard Lake USMC) Snuff films, rape, torture, enhanced interrogation: just like at Guantanamo Bay NATO: https://juxtaposition1.substack.com/p/project-miranda-leonard-lake-usmc Modus Operandi Between 1983 and 1985, Lake and Ng kidnapped, tortured, and murdered numerous individuals at a remote cabin in Wilseyville outside of WEST POINT California. Their typical approach involved abducting entire families, killing the men and children immediately, and subjecting the women to prolonged periods of sexual assault and torture before murdering them. They meticulously documented some of these atrocities through videotapes and journals, revealing the extent of their sadistic acts. Please subscribe to my Substack Channel: https://juxtaposition1.substack.com545 views

Juxtaposition1A Caste System prevails in all Hunger Game Districts worldwide. Scions (BANKERS, Landowner, Port Authorities, Maritime Law Courts) The Nobles, Judges, Chancellors, Popes, Cardinals, Bishops, Priests, CEOs) A Working Class The profane peasants Project Miranda, (Leonard Lake USMC) Snuff films, rape, torture, enhanced interrogation: just like at Guantanamo Bay NATO: https://juxtaposition1.substack.com/p/project-miranda-leonard-lake-usmc Modus Operandi Between 1983 and 1985, Lake and Ng kidnapped, tortured, and murdered numerous individuals at a remote cabin in Wilseyville outside of WEST POINT California. Their typical approach involved abducting entire families, killing the men and children immediately, and subjecting the women to prolonged periods of sexual assault and torture before murdering them. They meticulously documented some of these atrocities through videotapes and journals, revealing the extent of their sadistic acts. Please subscribe to my Substack Channel: https://juxtaposition1.substack.com545 views -

NATO Gladio killed JFK & sunk the USS Maine in the Port of Havana

Juxtaposition1Misty Mountain Hop (Who did it?) Led Zeppelin knew & so too does Juxtaposition: (NATO Gladio & SWISS Banks): https://juxtaposition1.substack.com/p/misty-mountain-hop-who-did-it Please subscribe to my Substack Channel: https://juxtaposition1.substack.com446 views 1 comment

Juxtaposition1Misty Mountain Hop (Who did it?) Led Zeppelin knew & so too does Juxtaposition: (NATO Gladio & SWISS Banks): https://juxtaposition1.substack.com/p/misty-mountain-hop-who-did-it Please subscribe to my Substack Channel: https://juxtaposition1.substack.com446 views 1 comment -

NATO Gladio kidnapped & murdered Emanuela Orlandi, age 15

Juxtaposition1Misty Mountain Hop (Who did it?) Led Zeppelin knew & so too does Juxtaposition: (NATO Gladio & SWISS Banks): https://juxtaposition1.substack.com/p/misty-mountain-hop-who-did-it Please subscribe to my Substack Channel: https://juxtaposition1.substack.com445 views 1 comment

Juxtaposition1Misty Mountain Hop (Who did it?) Led Zeppelin knew & so too does Juxtaposition: (NATO Gladio & SWISS Banks): https://juxtaposition1.substack.com/p/misty-mountain-hop-who-did-it Please subscribe to my Substack Channel: https://juxtaposition1.substack.com445 views 1 comment -

Operation Gladio Part 1: CIA, MI6, Subversive Activities & False Flag Operations

The Memory HoleThe secret history of the CIA: https://thememoryhole.substack.com/ Operation Gladio was the codename for clandestine "stay-behind" operations of armed resistance that were organized by the Western Union (WU) (founded in 1948), and subsequently by NATO (formed in 1949) and by the CIA (established in 1947),[1][2] in collaboration with several European intelligence agencies during the Cold War.[3] Although Gladio specifically refers to the Italian branch of the NATO stay-behind organizations, Operation Gladio is used as an informal name for all of them. Stay-behind operations were prepared in many NATO member countries, and in some neutral countries.[4] According to several Western European researchers, the operation involved the use of assassination, psychological warfare, and false flag operations to delegitimize left-wing parties in Western European countries, and even went so far as to support anti-communist militias and right-wing terrorism as they tortured communists and assassinated them, such as Eduardo Mondlane in 1969.[5][6][7][8] The United States Department of State rejected the view that they supported terrorists and maintains that the operation served only to resist a potential invasion of Western European countries by the Soviet Union.[9] History and general stay-behind structure British experience during World War II Following the fall of France in 1940, Winston Churchill created the Special Operations Executive (SOE) to both assist resistance movements and carry out sabotage and subversive operations in occupied Europe. It was revealed half a century later that SOE was complemented by a stay-behind organisation in Britain, created in extreme secrecy, to prepare for a possible invasion by Nazi Germany. A network of resistance fighters was formed across Britain and arms caches were established. The network was recruited, in part, from the 5th (Ski) Battalion of the Scots Guards (which had originally been formed, but was not deployed, to fight alongside Finnish forces fighting the Soviet invasion of Finland).[10] The network, which became known as the Auxiliary Units, was headed by Major Colin Gubbins – an expert in guerrilla warfare (who would later lead SOE). The units were trained, in part, by "Mad Mike" Calvert, a Royal Engineers officer who specialised in demolition by explosives and covert raiding operations. To the extent that they were publicly visible, the Auxiliary Units were disguised as Home Guard units, under GHQ Home Forces. The network was allegedly disbanded in 1944; some of its members subsequently joined the Special Air Service and saw action in North-West Europe. While David Lampe published a book on the Auxiliary Units in 1968,[11] their existence did not become widely known by the public until reporters such as David Pallister of The Guardian revived interest in them during the 1990s. Post-war creation After World War II, the UK and the US decided to create "stay-behind" paramilitary organizations, with the official aim of countering a possible Soviet invasion through sabotage and guerrilla warfare behind enemy lines. Arms caches were hidden, escape routes prepared, and loyal members recruited, whether in Italy or in other European countries. Its clandestine "cells" were to stay behind in enemy-controlled territory and to act as resistance movements, conducting sabotage, guerrilla warfare and assassinations. Clandestine stay-behind (SB) units were created with the experience and involvement of former SOE officers.[12] Following Giulio Andreotti's October 1990 revelations, General Sir John Hackett, former commander-in-chief of the British Army on the Rhine, declared on November 16, 1990, that a contingency plan involving "stay behind and resistance in depth" was drawn up after the war. The same week, Anthony Farrar-Hockley, former commander-in-chief of NATO's Forces in Northern Europe from 1979 to 1982, declared to The Guardian that a secret arms network was established in Britain after the war.[13] Hackett had written in 1978 a novel, The Third World War: August 1985, which was a fictionalized scenario of a Soviet Army invasion of West Germany in 1985. The novel was followed in 1982 by The Third World War: The Untold Story, which elaborated on the original. Farrar-Hockley had aroused controversy in 1983 when he became involved in trying to organise a campaign for a new Home Guard against a potential Soviet invasion.[14] NATO provided a forum to integrate, coordinate, and optimise the use of all SB assets as part of the Emergency War Plan. This coordination included the military SB units, which were part of NATO's order of battle, and the clandestine SBOs run by NATO nations. Western secret services had cooperated in various bilateral, triparty, and multilateral fora in the creation, training, and running of clandestine Stay-behind organisations (SBO) soon after World War II. In 1947, France, the United Kingdom, and the Benelux countries had created a joint policy on SB in the Western Union Clandestine Committee (WUCC), a forum of the Western Union, the European defence alliance predating NATO. The format entered into NATO structures around 1951–1952 when the Supreme Allied Commander in Europe (SACEUR) established such an 'ad hoc' committee, the Clandestine Planning Committee (CPC) at SHAPE. The peacetime role of the CPC would have been to coordinate the different military and paramilitary plans and programmes in NATO nations (and partners like Switzerland and Austria) in order to avoid duplication of effort. The CPC itself had at least two working groups – one on communications and one on networks. SACEUR also established a Special Projects Branch to develop and coordinate 'clandestine forces operating in support of SACEUR's military forces'.[15] In 1957, the United States, United Kingdom, France, and Benelux countries, all of which ran SBOs in Western Europe, established the 'Six Powers Lines Committee' which became the Allied Clandestine Committee in 1958 and, after 1976, the Allied Coordination Committee (ACC). The ACC has been described as a technical committee to bring national SBOs together. It took its guidance from the CPC and organized multinational exercises. The authority of SACEUR when it came to clandestine operations was discussed in the early 1950s as one can gather from the document 'SHAPE Problems Outstanding with the Standing Group', which, under sub-heading 'IV. Special Plans' calls for the 'Delineation of Responsibilities of the Clandestine Services and of SACEUR on Clandestine Matters Including Pertinent Definitions and Organizations' and 'Principles for Unorthodox Warfare Planning'. While all this concerned the highest level of NATO command, coordination in time of crisis had to be arranged. Thus, to coordinate these activities at different command levels in wartime, SACEUR created the Allied Clandestine Coordinating Groups (ACCG) staffed with personnel from NATO nations at SHAPE and the subordinate commands. In case of war, SACEUR was meant to exercise operational control of national clandestine services' assets, according to each nation's existing policies, through the ACCG. By 1961 though, 'both SHAPE and CPC [now] accepted that such SB activity [guerrilla warfare and resistance under Soviet occupation] was a purely national responsibility'.[16] Upon learning of the discovery, the parliament of the European Union (EU) drafted a resolution sharply criticizing the fact.[clarification needed] Yet only Italy, Belgium and Switzerland carried out parliamentary investigations, while the administration of President George H. W. Bush refused to comment.[17] NATO's "stay-behind" organizations were never called upon to resist a Soviet invasion. According to a November 13, 1990, Reuters cable,[18] "André Moyen – a former member of the Belgian military security service and of the [stay-behind] network – said Gladio was not just anti-Communist but was for fighting subversion in general. He added that his predecessor had given Gladio 142 million francs ($4.6 million) to buy new radio equipment."[19] Operations in NATO countries Italy The Italian NATO stay-behind organization, dubbed "Gladio", was set up under Minister of Defense (from 1953 to 1958) Paolo Taviani's (DC) supervision.[20] Gladio's existence came to public knowledge when Prime Minister Giulio Andreotti revealed it to the Chamber of Deputies on 24 October 1990, although far-right terrorist Vincenzo Vinciguerra had already revealed its existence during his 1984 trial. According to media analyst Edward S. Herman, "both the President of Italy, Francesco Cossiga, and Prime Minister Giulio Andreotti, had been involved in the Gladio organization and coverup ..."[21][22][23][verification needed] Researcher Francesco Cacciatore, in an article based on recently de-classified documents, writes that a "note from March 1972 specified that the possibility of using 'Gladio' in the event of internal subversions, not provided for by the organization's statute and not supported by NATO directives or plans, was outside the scope of the original stay-behind and, therefore, 'never to be considered among the purposes of the operation'. The pressure put forward by the Americans during the 1960s to use 'Gladio' for purposes other than those of a stay-behind network would appear to have failed in the long term."[24] According to the former Italian Ministry of Grace and Justice Claudio Martelli, during the 1980s and 1990s Andreotti was the political reference of Licio Gelli and the Masonic lodge Propaganda 2.[25] Giulio Andreotti's revelations on 24 October 1990 Christian Democrat Prime Minister Giulio Andreotti publicly recognized the existence of Gladio on 24 October 1990. Andreotti spoke of a "structure of information, response and safeguard", with arms caches and reserve officers. He gave to the Commissione Stragi[26] a list of 622 civilians who according to him were part of Gladio. Andreotti also stated that 127 weapons caches had been dismantled, and said that Gladio had not been involved in any of the bombings committed from the 1960s to the 1980s. Andreotti declared that the Italian military services (predecessors of the SISMI) had joined in 1964 the Allied Clandestine Committee created in 1957 by the US, France, Belgium and Greece, and which was in charge of directing Gladio's operations.[27] However, Gladio was actually set up under Minister of Defence (from 1953 to 1958) Paolo Taviani's supervision.[20] Besides, the list of Gladio members given by Andreotti was incomplete. It didn't include, for example, Antonio Arconte, who described an organization very different from the one brushed by Giulio Andreotti: an organization closely tied to the SID secret service and the Atlanticist strategy.[28][29] According to Andreotti, the stay-behind organisations set up in all of Europe did not come "under broad NATO supervision until 1959."[30] Judicial Inquiries The judge Guido Salvini, who worked in the Italian Massacres Commission, found out that several far-right terrorist organizations were the trench troops of a secret army who were linked to the CIA.[31] Salvini said: "The role of the Americans was ambiguous, halfway between knowing and not preventing and actually inducing people to commit atrocities".[32] Judge Gerardo D'Ambrosio found out that in a conference that had the patronage of the Chief Staff of Defense, there were instructions to infiltrate left-wing groups and provoke social tension by carrying out attacks and then blame them on the left.[33] 2000 parliamentary report and the strategy of tension In 2000, a parliamentary commission report from the left-wing coalition Gruppo Democratici di Sinistra l'Ulivo asserted that a strategy of tension had been supported by the United States to "stop the PCI, and to a certain degree also the PSI, from reaching executive power in the country". It stated that "Those massacres, those bombs, those military actions had been organized or promoted or supported by men inside Italian state institutions and, as has been discovered more recently, by men linked to the structures of United States intelligence." The report stated that US intelligence agents were informed in advance about several terrorist bombings, including the December 1969 Piazza Fontana bombing in Milan and the Piazza della Loggia bombing in Brescia five years later, but did nothing to alert the Italian authorities or to prevent the attacks from taking place. It also reported that Pino Rauti, former leader of the MSI Fiamma-Tricolore party, journalist and founder of the Ordine Nuovo (new order) subversive organisation, received regular funding from a press officer at the US embassy in Rome. 'So even before the 'stabilising' plans that Atlantic circles had prepared for Italy became operational through the bombings, one of the leading members of the terrorist group was in the pay of the American embassy in Rome.' a report released by the Democrats of the Left party says.[34] General Serravalle's statements General Gerardo Serravalle, who commanded the Italian Gladio from 1971 to 1974, related that "in the 1970s the members of the CPC [Coordination and Planning Committee] were the officers responsible for the secret structures of Great Britain, France, Germany, Belgium, Luxembourg, the Netherlands and Italy. These representatives of the secret structures met every year in one of the capitals... At the stay-behind meetings representatives of the CIA were always present. They had no voting rights and were from the CIA headquarters of the capital in which the meeting took place... members of the US Forces Europe Command were present, also without voting rights. "[35] Next to the CPC a second secret command post was created in 1957, the Allied Clandestine Committee (ACC). According to the Belgian Parliamentary Committee on Gladio, the ACC was "responsible for coordinating the 'Stay-behind' networks in Belgium, Denmark, France, Germany, Italy, Luxembourg, Holland, Norway, United Kingdom and the United States". During peacetime, the activities of the ACC "included elaborating the directives for the network, developing its clandestine capability and organising bases in Britain and the United States. In wartime, it was to plan stay-behind operations in conjunction with SHAPE; organisers were to activate clandestine bases and organise operations from there".[36] General Serravalle declared to the Commissione Stragi headed by senator Giovanni Pellegrino that the Italian Gladio members trained at a military base in Britain.[13] Belgium Main article: Belgian stay-behind network After the 1967 withdrawal of France from NATO's military structure, the SHAPE headquarters were displaced to Mons in Belgium. In 1990, following France's denial of any "stay-behind" French army, Giulio Andreotti publicly said the last Allied Clandestine Committee (ACC) meeting, at which the French branch of Gladio was present, had been on October 23 and 24, 1990, under the presidency of Belgian General Van Calster, director of the Belgian military General Service for Intelligence (SGR). In November, Guy Coëme, the Minister of Defense, acknowledged the existence of a Belgian "stay-behind" army, raising concerns about a similar implication in terrorist acts as in Italy. The same year, the European Parliament sharply condemned NATO and the United States in a resolution for having manipulated European politics with the stay-behind armies.[12][37] New legislation governing intelligence agencies' missions and methods was passed in 1998, following two government inquiries and the creation of a permanent parliamentary committee in 1991, which was to bring them under the authority of Belgium's federal agencies. The commission was created following events in the 1980s, which included the Brabant massacres and the activities of the far-right group Westland New Post.[38] Denmark The Danish stay-behind army was code-named Absalon, after a Danish archbishop, and led by E. J. Harder. It was hidden in the military secret service Forsvarets Efterretningstjeneste (FE). In 1978, William Colby, former director of the CIA, released his memoirs in which he described the setting-up of stay-behind armies in Scandinavia:[39] The situation in each Scandinavian country was different. Norway and Denmark were NATO allies, Sweden held to the neutrality that had taken her through two world wars, and Finland were required to defer in its foreign policy to the Soviet power directly on its borders. Thus, in one set of these countries the governments themselves would build their own stay-behind nets, counting on activating them from exile to carry on the struggle. These nets had to be co-ordinated with NATO's plans, their radios had to be hooked to a future exile location, and the specialised equipment had to be secured from CIA and secretly cached in snowy hideouts for later use. In the other set of countries, CIA would have to do the job alone or with, at best, "unofficial" local help, since the politics of those governments barred them from collaborating with NATO, and any exposure would arouse immediate protest from the local Communist press, Soviet diplomats and loyal Scandinavians who hoped that neutrality or nonalignment would allow them to slip through a World War III unharmed. France In 1947, Interior Minister Édouard Depreux revealed the existence of a secret stay-behind army in France codenamed "Plan Bleu". The next year, the "Western Union Clandestine Committee" (WUCC) was created to coordinate secret unorthodox warfare. In 1949, the WUCC was integrated into NATO, whose headquarters were established in France, under the name "Clandestine Planning Committee" (CPC). In 1958, NATO founded the Allied Clandestine Committee (ACC) to coordinate secret warfare.[40] The network was supported with elements from SDECE, and had military support from the 11th Choc regiment. The former director of DGSE, Admiral Pierre Lacoste, alleged in a 1992 interview with The Nation, that certain elements from the network were involved in terrorist activities against de Gaulle and his Algerian policy. A section of the 11th Choc regiment split over the 1962 Évian peace accords, and became part of the Organisation armée secrète (OAS), but it is unclear if this also involved members of the French stay-behind network.[41][42] La Rose des Vents and Arc-en-ciel ("Rainbow") network were part of Gladio.[43] François de Grossouvre was Gladio's leader for the region around Lyon in France until his alleged suicide on April 7, 1994. Grossouvre would have asked Constantin Melnik, leader of the French secret services during the Algerian War of Independence (1954–62), to return to activity. He was living in comfortable exile in the US, where he maintained links with the Rand Corporation. Constantin Melnik is alleged to have been involved in the creation in 1952 of the Ordre Souverain du Temple Solaire, an ancestor of the Order of the Solar Temple, created by former A.M.O.R.C. members, in which the SDECE (French former military intelligence agency) was interested.[44] Germany US intelligence also assisted in the set up of a West German stay-behind network. CIA documents released in June 2006 under the 1998 Nazi War Crimes Disclosure Act, show that the CIA organized "stay-behind" networks of West German agents between 1949 and 1953. According to The Washington Post, "One network included at least two former Nazi SS members—Staff Sgt. Heinrich Hoffman and Lt. Col. Hans Rues—and one was run by Lt. Col. Walter Kopp, a former German army officer referred to by the CIA as an "unreconstructed Nazi". "The network was disbanded in 1953 amid political concerns that some members' neo-Nazi sympathies would be exposed in the West German press."[45] Documents shown to the Italian parliamentary terrorism committee revealed that in the 1970s British and French officials involved in the network visited a training base in Germany built with US money.[13] In 1976, West German secret service BND secretary Heidrun Hofer was arrested after having revealed the secrets of the West German stay-behind army to her husband, who was a spy of the KGB.[12] In 2004 the German author Norbert Juretzko published a book about his work at the BND. He went into details about recruiting partisans for the German stay-behind network. He was sacked from BND following a secret trial against him because the BND could not find out the real name of his Russian source "Rübezahl" whom he had recruited. A man with the name he put on file was arrested by the KGB following treason in the BND, but was obviously innocent, his name having been chosen at random from the public phone book by Juretzko.[citation needed] According to Juretzko, the BND built up its branch of Gladio, but discovered after the fall of the German Democratic Republic that it was fully known to the Stasi early on. When the network was dismantled, further odd details emerged. One fellow "spymaster" had kept the radio equipment in his cellar at home with his wife doing the engineering test call every four months, on the grounds that the equipment was too "valuable" to remain in civilian hands. Juretzko found out because this spymaster had dismantled his section of the network so quickly, there had been no time for measures such as recovering all caches of supplies.[citation needed] Civilians recruited as stay-behind partisans were equipped with a clandestine shortwave radio homed in on a fixed frequency. It had a keyboard with digital encryption, making use of traditional Morse code obsolete. They had a cache of further equipment for signalling helicopters or submarines to drop special agents who were to stay in the partisan's homes while mounting sabotage operations against the communists. Greece When Greece joined NATO in 1952, the country's special forces, LOK (Lochoi Oreinōn Katadromōn, i.e., "mountain raiding companies"), were integrated into the European stay-behind network. The CIA and LOK reconfirmed on March 25, 1955, their mutual cooperation in a secret document signed by US General Truscott for the CIA, and Konstantinos Dovas, chief of staff of the Greek military. In addition to preparing for a Soviet invasion, the CIA instructed LOK to prevent a leftist coup. Former CIA agent Philip Agee, who was sharply criticized in the US for having revealed sensitive information, insisted that "paramilitary groups, directed by CIA officers, operated in the sixties throughout Europe [and he stressed that] perhaps no activity of the CIA could be as clearly linked to the possibility of internal subversion."[46] According to Ilektra, LOK was involved in the military coup d'état on 21 April 1967,[47]: 221 which took place one month before the scheduled national elections. Under the command of paratrooper Lieutenant Colonel Costas Aslanides, LOK took control of the Greek Defence Ministry while Brigadier General Stylianos Pattakos gained control of communication centres, parliament, the royal palace, and according to detailed lists, arrested over 10,000 people. According to Ganser, Phillips Talbot, the US ambassador in Athens, disapproved of the military coup which established the "Regime of the Colonels" (1967–1974), complaining that it represented "a rape of democracy"—to which Jack Maury, the CIA chief of station in Athens, answered, "How can you rape a whore?"[47]: 221 Arrested and then exiled in Canada and Sweden, Andreas Papandreou later returned to Greece, where he won the 1981 election, forming the first socialist government of Greece's post-war history. According to his own testimony, Ganser alleges, he discovered the existence of the secret NATO army, then codenamed "Red Sheepskin", as acting prime minister in 1984 and had given orders to dissolve it.[47]: 223 Following Giulio Andreotti's revelations in 1990, the Greek defence minister confirmed that a branch of the network, known as Operation Sheepskin, operated in his country until 1988.[48] In December 2005, journalist Kleanthis Grivas published an article in To Proto Thema, a Greek Sunday newspaper, in which he accused "Sheepskin" for the assassination of CIA station chief Richard Welch in Athens in 1975, as well as the assassination of British military attaché Stephen Saunders in 2000. This was denied by the US State Department, who responded that "the Greek terrorist organization '17 November' was responsible for both assassinations", and that Grivas's central piece of evidence had been the Westmoreland Field Manual which the state department, as well as an independent congressional inquiry, have alleged to be a Soviet forgery.[49] The State Department also highlighted the fact that, in the case of Richard Welch, "Grivas bizarrely accuses the CIA of playing a role in the assassination of one of its own senior officials" while "Sheepskin" couldn't have assassinated Stephen Saunders for the simple reason that, according to the US government, "the Greek government stated it dismantled the 'stay behind' network in 1988."[49] Netherlands Speculation that the Netherlands was involved in Gladio arose from the accidental discovery of large arms caches in 1980 and 1983.[50] In the latter incident, people walking in a forest near the village of Rozendaal, near Arnhem, chanced upon a large hidden cache of arms, containing dozens of hand grenades, semiautomatic rifles, automatic pistols, munitions and explosives.[51][52] That discovery forced the Dutch government to confirm that the arms were related to NATO planning for unorthodox warfare.[53] In 1990, then-Prime Minister Ruud Lubbers told the Dutch Parliament that his office was running a secret organisation that had been set up inside the Dutch defence ministry in the 1950s, but denied it was supervised directly by NATO or other foreign bodies. He went on to inform that successive prime ministers and defence chiefs had always preferred not to inform other Cabinet members or Parliament about the secret organization. It was modelled on the nation's World War II experiences of having to evacuate the royal family and transfer government to a government-in-exile,[52] originally aiming to provide an underground intelligence network to a government-in-exile in the event of a foreign invasion, although it included elements of guerilla warfare. Former Dutch Defence Minister Henk Vredeling confirmed the group had set up arms caches around the Netherlands for sabotage purposes.[52] Already in 1990, it was known that the weapons cache near Velp, while accidentally 'discovered' in 1983, had been plundered partially before. It still contained dozens of hand grenades, semiautomatic rifles, automatic pistols, munitions and explosives at the time of discovery, but five hand grenades had gone missing.[52] A Dutch investigative television program revealed on 9 September 2007, that another arms cache that had belonged to Gladio had been ransacked in the 1980s. It was located in a park near Scheveningen. Some of the stolen weapons, including hand grenades and machine guns, later turned up when police officials arrested criminals John Mieremet and Sam Klepper in 1991. The Dutch military intelligence agency MIVD feared at the time that disclosure of the Gladio history of these weapons would have been politically sensitive.[54][55] Norway In 1957, the director of the secret service NIS, Vilhelm Evang, protested strongly against the pro-active intelligence activities at AFNORTH, as described by the chairman of CPC: "[NIS] was extremely worried about activities carried out by officers at Kolsås. This concerned SB, Psywar and Counter Intelligence." These activities supposedly included the blacklisting of Norwegians. SHAPE denied these allegations. Eventually, the matter was resolved in 1958, after Norway was assured about how stay-behind networks were to be operated.[56] In 1978, the police discovered an arms cache and radio equipment at a mountain cabin and arrested Hans Otto Meyer (no), a businessman accused of being involved in selling illegal alcohol. Meyer claimed that the weapons were supplied by Norwegian intelligence. Rolf Hansen, defence minister at that time, stated the network was not in any way answerable to NATO and had no CIA connection.[57] Portugal Further information: Aginter Press In 1966, the CIA set up Aginter Press which, under the direction of Captain Yves Guérin-Sérac (who had taken part in the founding of the OAS), ran a secret stay-behind army and trained its members in covert action techniques amounting to terrorism, including bombings, silent assassinations, subversion techniques, clandestine communication and infiltration and colonial warfare.[12] Turkey Main article: Counter-Guerrilla See also: Ergenekon (allegation), Deep state in Turkey, 1980 Turkish coup d'état, and Ruzi Nazar In an excerpt from Mehtap Söyler's 2015 book entitled The Turkish Deep State: State Consolidation, Civil-Military Relations and Democracy, Söyler details how certain Western forces encouraged Turkish nationalism via Operation Gladio. Specifically, Operation Gladio empowered Turanism through the founding member of the Counter-Guerrilla; Alparslan Türkeş — a product of that CIA initiative.[58] As one of the nations that prompted the Truman Doctrine, Turkey is one of the first countries to participate in Operation Gladio and, some[who?] say, the only country where it has not been purged.[59] The counter-guerrillas' existence in Turkey was revealed in 1973 by then-prime minister Bülent Ecevit.[60] General Kenan Evren, who became President of Turkey following a successful coup d'état in 1980, served as the head of the Counter-Guerrilla, the Turkish branch of Operation Gladio. Historians and outside investigators have speculated that Counter-Guerrilla and several subordinate Intelligence, Special Forces, and Gendarmerie units were possibly involved in numerous acts of state-sponsored terrorism and engineering the military coups of 1971 and 1980. Many of the high ranking plotters of the 1971 and 1980 coup, such as Generals Evren, Memduh Tağmaç, Faik Türün, Sabri Yirmibeşoğlu, Kemal Yamak and Air Force Commander Tahsin Şahinkaya served at various times under the command of Counter-Guerrilla or the subordinate Tactical Mobilisation Group and Special Warfare Department. Additionally, the CIA employed people from the far-right, such as Pan-Turkist SS-member Ruzi Nazar (father of Sylvia Nasar),[61] to train the Grey Wolves (Turkish: Ülkücüler),[62] the youth wing of the MHP. Nazar was an Uzbek born near Tashkent who had deserted the Red Army to join the Nazis during World War II in order to fight on the Eastern Front for the creation of a Turkistan.[63] After Germany lost the war, some of its spies found haven in the U.S. intelligence community. Nazar was such a person, and he became the CIA's station chief to Turkey.[64]2.42K views 1 comment

The Memory HoleThe secret history of the CIA: https://thememoryhole.substack.com/ Operation Gladio was the codename for clandestine "stay-behind" operations of armed resistance that were organized by the Western Union (WU) (founded in 1948), and subsequently by NATO (formed in 1949) and by the CIA (established in 1947),[1][2] in collaboration with several European intelligence agencies during the Cold War.[3] Although Gladio specifically refers to the Italian branch of the NATO stay-behind organizations, Operation Gladio is used as an informal name for all of them. Stay-behind operations were prepared in many NATO member countries, and in some neutral countries.[4] According to several Western European researchers, the operation involved the use of assassination, psychological warfare, and false flag operations to delegitimize left-wing parties in Western European countries, and even went so far as to support anti-communist militias and right-wing terrorism as they tortured communists and assassinated them, such as Eduardo Mondlane in 1969.[5][6][7][8] The United States Department of State rejected the view that they supported terrorists and maintains that the operation served only to resist a potential invasion of Western European countries by the Soviet Union.[9] History and general stay-behind structure British experience during World War II Following the fall of France in 1940, Winston Churchill created the Special Operations Executive (SOE) to both assist resistance movements and carry out sabotage and subversive operations in occupied Europe. It was revealed half a century later that SOE was complemented by a stay-behind organisation in Britain, created in extreme secrecy, to prepare for a possible invasion by Nazi Germany. A network of resistance fighters was formed across Britain and arms caches were established. The network was recruited, in part, from the 5th (Ski) Battalion of the Scots Guards (which had originally been formed, but was not deployed, to fight alongside Finnish forces fighting the Soviet invasion of Finland).[10] The network, which became known as the Auxiliary Units, was headed by Major Colin Gubbins – an expert in guerrilla warfare (who would later lead SOE). The units were trained, in part, by "Mad Mike" Calvert, a Royal Engineers officer who specialised in demolition by explosives and covert raiding operations. To the extent that they were publicly visible, the Auxiliary Units were disguised as Home Guard units, under GHQ Home Forces. The network was allegedly disbanded in 1944; some of its members subsequently joined the Special Air Service and saw action in North-West Europe. While David Lampe published a book on the Auxiliary Units in 1968,[11] their existence did not become widely known by the public until reporters such as David Pallister of The Guardian revived interest in them during the 1990s. Post-war creation After World War II, the UK and the US decided to create "stay-behind" paramilitary organizations, with the official aim of countering a possible Soviet invasion through sabotage and guerrilla warfare behind enemy lines. Arms caches were hidden, escape routes prepared, and loyal members recruited, whether in Italy or in other European countries. Its clandestine "cells" were to stay behind in enemy-controlled territory and to act as resistance movements, conducting sabotage, guerrilla warfare and assassinations. Clandestine stay-behind (SB) units were created with the experience and involvement of former SOE officers.[12] Following Giulio Andreotti's October 1990 revelations, General Sir John Hackett, former commander-in-chief of the British Army on the Rhine, declared on November 16, 1990, that a contingency plan involving "stay behind and resistance in depth" was drawn up after the war. The same week, Anthony Farrar-Hockley, former commander-in-chief of NATO's Forces in Northern Europe from 1979 to 1982, declared to The Guardian that a secret arms network was established in Britain after the war.[13] Hackett had written in 1978 a novel, The Third World War: August 1985, which was a fictionalized scenario of a Soviet Army invasion of West Germany in 1985. The novel was followed in 1982 by The Third World War: The Untold Story, which elaborated on the original. Farrar-Hockley had aroused controversy in 1983 when he became involved in trying to organise a campaign for a new Home Guard against a potential Soviet invasion.[14] NATO provided a forum to integrate, coordinate, and optimise the use of all SB assets as part of the Emergency War Plan. This coordination included the military SB units, which were part of NATO's order of battle, and the clandestine SBOs run by NATO nations. Western secret services had cooperated in various bilateral, triparty, and multilateral fora in the creation, training, and running of clandestine Stay-behind organisations (SBO) soon after World War II. In 1947, France, the United Kingdom, and the Benelux countries had created a joint policy on SB in the Western Union Clandestine Committee (WUCC), a forum of the Western Union, the European defence alliance predating NATO. The format entered into NATO structures around 1951–1952 when the Supreme Allied Commander in Europe (SACEUR) established such an 'ad hoc' committee, the Clandestine Planning Committee (CPC) at SHAPE. The peacetime role of the CPC would have been to coordinate the different military and paramilitary plans and programmes in NATO nations (and partners like Switzerland and Austria) in order to avoid duplication of effort. The CPC itself had at least two working groups – one on communications and one on networks. SACEUR also established a Special Projects Branch to develop and coordinate 'clandestine forces operating in support of SACEUR's military forces'.[15] In 1957, the United States, United Kingdom, France, and Benelux countries, all of which ran SBOs in Western Europe, established the 'Six Powers Lines Committee' which became the Allied Clandestine Committee in 1958 and, after 1976, the Allied Coordination Committee (ACC). The ACC has been described as a technical committee to bring national SBOs together. It took its guidance from the CPC and organized multinational exercises. The authority of SACEUR when it came to clandestine operations was discussed in the early 1950s as one can gather from the document 'SHAPE Problems Outstanding with the Standing Group', which, under sub-heading 'IV. Special Plans' calls for the 'Delineation of Responsibilities of the Clandestine Services and of SACEUR on Clandestine Matters Including Pertinent Definitions and Organizations' and 'Principles for Unorthodox Warfare Planning'. While all this concerned the highest level of NATO command, coordination in time of crisis had to be arranged. Thus, to coordinate these activities at different command levels in wartime, SACEUR created the Allied Clandestine Coordinating Groups (ACCG) staffed with personnel from NATO nations at SHAPE and the subordinate commands. In case of war, SACEUR was meant to exercise operational control of national clandestine services' assets, according to each nation's existing policies, through the ACCG. By 1961 though, 'both SHAPE and CPC [now] accepted that such SB activity [guerrilla warfare and resistance under Soviet occupation] was a purely national responsibility'.[16] Upon learning of the discovery, the parliament of the European Union (EU) drafted a resolution sharply criticizing the fact.[clarification needed] Yet only Italy, Belgium and Switzerland carried out parliamentary investigations, while the administration of President George H. W. Bush refused to comment.[17] NATO's "stay-behind" organizations were never called upon to resist a Soviet invasion. According to a November 13, 1990, Reuters cable,[18] "André Moyen – a former member of the Belgian military security service and of the [stay-behind] network – said Gladio was not just anti-Communist but was for fighting subversion in general. He added that his predecessor had given Gladio 142 million francs ($4.6 million) to buy new radio equipment."[19] Operations in NATO countries Italy The Italian NATO stay-behind organization, dubbed "Gladio", was set up under Minister of Defense (from 1953 to 1958) Paolo Taviani's (DC) supervision.[20] Gladio's existence came to public knowledge when Prime Minister Giulio Andreotti revealed it to the Chamber of Deputies on 24 October 1990, although far-right terrorist Vincenzo Vinciguerra had already revealed its existence during his 1984 trial. According to media analyst Edward S. Herman, "both the President of Italy, Francesco Cossiga, and Prime Minister Giulio Andreotti, had been involved in the Gladio organization and coverup ..."[21][22][23][verification needed] Researcher Francesco Cacciatore, in an article based on recently de-classified documents, writes that a "note from March 1972 specified that the possibility of using 'Gladio' in the event of internal subversions, not provided for by the organization's statute and not supported by NATO directives or plans, was outside the scope of the original stay-behind and, therefore, 'never to be considered among the purposes of the operation'. The pressure put forward by the Americans during the 1960s to use 'Gladio' for purposes other than those of a stay-behind network would appear to have failed in the long term."[24] According to the former Italian Ministry of Grace and Justice Claudio Martelli, during the 1980s and 1990s Andreotti was the political reference of Licio Gelli and the Masonic lodge Propaganda 2.[25] Giulio Andreotti's revelations on 24 October 1990 Christian Democrat Prime Minister Giulio Andreotti publicly recognized the existence of Gladio on 24 October 1990. Andreotti spoke of a "structure of information, response and safeguard", with arms caches and reserve officers. He gave to the Commissione Stragi[26] a list of 622 civilians who according to him were part of Gladio. Andreotti also stated that 127 weapons caches had been dismantled, and said that Gladio had not been involved in any of the bombings committed from the 1960s to the 1980s. Andreotti declared that the Italian military services (predecessors of the SISMI) had joined in 1964 the Allied Clandestine Committee created in 1957 by the US, France, Belgium and Greece, and which was in charge of directing Gladio's operations.[27] However, Gladio was actually set up under Minister of Defence (from 1953 to 1958) Paolo Taviani's supervision.[20] Besides, the list of Gladio members given by Andreotti was incomplete. It didn't include, for example, Antonio Arconte, who described an organization very different from the one brushed by Giulio Andreotti: an organization closely tied to the SID secret service and the Atlanticist strategy.[28][29] According to Andreotti, the stay-behind organisations set up in all of Europe did not come "under broad NATO supervision until 1959."[30] Judicial Inquiries The judge Guido Salvini, who worked in the Italian Massacres Commission, found out that several far-right terrorist organizations were the trench troops of a secret army who were linked to the CIA.[31] Salvini said: "The role of the Americans was ambiguous, halfway between knowing and not preventing and actually inducing people to commit atrocities".[32] Judge Gerardo D'Ambrosio found out that in a conference that had the patronage of the Chief Staff of Defense, there were instructions to infiltrate left-wing groups and provoke social tension by carrying out attacks and then blame them on the left.[33] 2000 parliamentary report and the strategy of tension In 2000, a parliamentary commission report from the left-wing coalition Gruppo Democratici di Sinistra l'Ulivo asserted that a strategy of tension had been supported by the United States to "stop the PCI, and to a certain degree also the PSI, from reaching executive power in the country". It stated that "Those massacres, those bombs, those military actions had been organized or promoted or supported by men inside Italian state institutions and, as has been discovered more recently, by men linked to the structures of United States intelligence." The report stated that US intelligence agents were informed in advance about several terrorist bombings, including the December 1969 Piazza Fontana bombing in Milan and the Piazza della Loggia bombing in Brescia five years later, but did nothing to alert the Italian authorities or to prevent the attacks from taking place. It also reported that Pino Rauti, former leader of the MSI Fiamma-Tricolore party, journalist and founder of the Ordine Nuovo (new order) subversive organisation, received regular funding from a press officer at the US embassy in Rome. 'So even before the 'stabilising' plans that Atlantic circles had prepared for Italy became operational through the bombings, one of the leading members of the terrorist group was in the pay of the American embassy in Rome.' a report released by the Democrats of the Left party says.[34] General Serravalle's statements General Gerardo Serravalle, who commanded the Italian Gladio from 1971 to 1974, related that "in the 1970s the members of the CPC [Coordination and Planning Committee] were the officers responsible for the secret structures of Great Britain, France, Germany, Belgium, Luxembourg, the Netherlands and Italy. These representatives of the secret structures met every year in one of the capitals... At the stay-behind meetings representatives of the CIA were always present. They had no voting rights and were from the CIA headquarters of the capital in which the meeting took place... members of the US Forces Europe Command were present, also without voting rights. "[35] Next to the CPC a second secret command post was created in 1957, the Allied Clandestine Committee (ACC). According to the Belgian Parliamentary Committee on Gladio, the ACC was "responsible for coordinating the 'Stay-behind' networks in Belgium, Denmark, France, Germany, Italy, Luxembourg, Holland, Norway, United Kingdom and the United States". During peacetime, the activities of the ACC "included elaborating the directives for the network, developing its clandestine capability and organising bases in Britain and the United States. In wartime, it was to plan stay-behind operations in conjunction with SHAPE; organisers were to activate clandestine bases and organise operations from there".[36] General Serravalle declared to the Commissione Stragi headed by senator Giovanni Pellegrino that the Italian Gladio members trained at a military base in Britain.[13] Belgium Main article: Belgian stay-behind network After the 1967 withdrawal of France from NATO's military structure, the SHAPE headquarters were displaced to Mons in Belgium. In 1990, following France's denial of any "stay-behind" French army, Giulio Andreotti publicly said the last Allied Clandestine Committee (ACC) meeting, at which the French branch of Gladio was present, had been on October 23 and 24, 1990, under the presidency of Belgian General Van Calster, director of the Belgian military General Service for Intelligence (SGR). In November, Guy Coëme, the Minister of Defense, acknowledged the existence of a Belgian "stay-behind" army, raising concerns about a similar implication in terrorist acts as in Italy. The same year, the European Parliament sharply condemned NATO and the United States in a resolution for having manipulated European politics with the stay-behind armies.[12][37] New legislation governing intelligence agencies' missions and methods was passed in 1998, following two government inquiries and the creation of a permanent parliamentary committee in 1991, which was to bring them under the authority of Belgium's federal agencies. The commission was created following events in the 1980s, which included the Brabant massacres and the activities of the far-right group Westland New Post.[38] Denmark The Danish stay-behind army was code-named Absalon, after a Danish archbishop, and led by E. J. Harder. It was hidden in the military secret service Forsvarets Efterretningstjeneste (FE). In 1978, William Colby, former director of the CIA, released his memoirs in which he described the setting-up of stay-behind armies in Scandinavia:[39] The situation in each Scandinavian country was different. Norway and Denmark were NATO allies, Sweden held to the neutrality that had taken her through two world wars, and Finland were required to defer in its foreign policy to the Soviet power directly on its borders. Thus, in one set of these countries the governments themselves would build their own stay-behind nets, counting on activating them from exile to carry on the struggle. These nets had to be co-ordinated with NATO's plans, their radios had to be hooked to a future exile location, and the specialised equipment had to be secured from CIA and secretly cached in snowy hideouts for later use. In the other set of countries, CIA would have to do the job alone or with, at best, "unofficial" local help, since the politics of those governments barred them from collaborating with NATO, and any exposure would arouse immediate protest from the local Communist press, Soviet diplomats and loyal Scandinavians who hoped that neutrality or nonalignment would allow them to slip through a World War III unharmed. France In 1947, Interior Minister Édouard Depreux revealed the existence of a secret stay-behind army in France codenamed "Plan Bleu". The next year, the "Western Union Clandestine Committee" (WUCC) was created to coordinate secret unorthodox warfare. In 1949, the WUCC was integrated into NATO, whose headquarters were established in France, under the name "Clandestine Planning Committee" (CPC). In 1958, NATO founded the Allied Clandestine Committee (ACC) to coordinate secret warfare.[40] The network was supported with elements from SDECE, and had military support from the 11th Choc regiment. The former director of DGSE, Admiral Pierre Lacoste, alleged in a 1992 interview with The Nation, that certain elements from the network were involved in terrorist activities against de Gaulle and his Algerian policy. A section of the 11th Choc regiment split over the 1962 Évian peace accords, and became part of the Organisation armée secrète (OAS), but it is unclear if this also involved members of the French stay-behind network.[41][42] La Rose des Vents and Arc-en-ciel ("Rainbow") network were part of Gladio.[43] François de Grossouvre was Gladio's leader for the region around Lyon in France until his alleged suicide on April 7, 1994. Grossouvre would have asked Constantin Melnik, leader of the French secret services during the Algerian War of Independence (1954–62), to return to activity. He was living in comfortable exile in the US, where he maintained links with the Rand Corporation. Constantin Melnik is alleged to have been involved in the creation in 1952 of the Ordre Souverain du Temple Solaire, an ancestor of the Order of the Solar Temple, created by former A.M.O.R.C. members, in which the SDECE (French former military intelligence agency) was interested.[44] Germany US intelligence also assisted in the set up of a West German stay-behind network. CIA documents released in June 2006 under the 1998 Nazi War Crimes Disclosure Act, show that the CIA organized "stay-behind" networks of West German agents between 1949 and 1953. According to The Washington Post, "One network included at least two former Nazi SS members—Staff Sgt. Heinrich Hoffman and Lt. Col. Hans Rues—and one was run by Lt. Col. Walter Kopp, a former German army officer referred to by the CIA as an "unreconstructed Nazi". "The network was disbanded in 1953 amid political concerns that some members' neo-Nazi sympathies would be exposed in the West German press."[45] Documents shown to the Italian parliamentary terrorism committee revealed that in the 1970s British and French officials involved in the network visited a training base in Germany built with US money.[13] In 1976, West German secret service BND secretary Heidrun Hofer was arrested after having revealed the secrets of the West German stay-behind army to her husband, who was a spy of the KGB.[12] In 2004 the German author Norbert Juretzko published a book about his work at the BND. He went into details about recruiting partisans for the German stay-behind network. He was sacked from BND following a secret trial against him because the BND could not find out the real name of his Russian source "Rübezahl" whom he had recruited. A man with the name he put on file was arrested by the KGB following treason in the BND, but was obviously innocent, his name having been chosen at random from the public phone book by Juretzko.[citation needed] According to Juretzko, the BND built up its branch of Gladio, but discovered after the fall of the German Democratic Republic that it was fully known to the Stasi early on. When the network was dismantled, further odd details emerged. One fellow "spymaster" had kept the radio equipment in his cellar at home with his wife doing the engineering test call every four months, on the grounds that the equipment was too "valuable" to remain in civilian hands. Juretzko found out because this spymaster had dismantled his section of the network so quickly, there had been no time for measures such as recovering all caches of supplies.[citation needed] Civilians recruited as stay-behind partisans were equipped with a clandestine shortwave radio homed in on a fixed frequency. It had a keyboard with digital encryption, making use of traditional Morse code obsolete. They had a cache of further equipment for signalling helicopters or submarines to drop special agents who were to stay in the partisan's homes while mounting sabotage operations against the communists. Greece When Greece joined NATO in 1952, the country's special forces, LOK (Lochoi Oreinōn Katadromōn, i.e., "mountain raiding companies"), were integrated into the European stay-behind network. The CIA and LOK reconfirmed on March 25, 1955, their mutual cooperation in a secret document signed by US General Truscott for the CIA, and Konstantinos Dovas, chief of staff of the Greek military. In addition to preparing for a Soviet invasion, the CIA instructed LOK to prevent a leftist coup. Former CIA agent Philip Agee, who was sharply criticized in the US for having revealed sensitive information, insisted that "paramilitary groups, directed by CIA officers, operated in the sixties throughout Europe [and he stressed that] perhaps no activity of the CIA could be as clearly linked to the possibility of internal subversion."[46] According to Ilektra, LOK was involved in the military coup d'état on 21 April 1967,[47]: 221 which took place one month before the scheduled national elections. Under the command of paratrooper Lieutenant Colonel Costas Aslanides, LOK took control of the Greek Defence Ministry while Brigadier General Stylianos Pattakos gained control of communication centres, parliament, the royal palace, and according to detailed lists, arrested over 10,000 people. According to Ganser, Phillips Talbot, the US ambassador in Athens, disapproved of the military coup which established the "Regime of the Colonels" (1967–1974), complaining that it represented "a rape of democracy"—to which Jack Maury, the CIA chief of station in Athens, answered, "How can you rape a whore?"[47]: 221 Arrested and then exiled in Canada and Sweden, Andreas Papandreou later returned to Greece, where he won the 1981 election, forming the first socialist government of Greece's post-war history. According to his own testimony, Ganser alleges, he discovered the existence of the secret NATO army, then codenamed "Red Sheepskin", as acting prime minister in 1984 and had given orders to dissolve it.[47]: 223 Following Giulio Andreotti's revelations in 1990, the Greek defence minister confirmed that a branch of the network, known as Operation Sheepskin, operated in his country until 1988.[48] In December 2005, journalist Kleanthis Grivas published an article in To Proto Thema, a Greek Sunday newspaper, in which he accused "Sheepskin" for the assassination of CIA station chief Richard Welch in Athens in 1975, as well as the assassination of British military attaché Stephen Saunders in 2000. This was denied by the US State Department, who responded that "the Greek terrorist organization '17 November' was responsible for both assassinations", and that Grivas's central piece of evidence had been the Westmoreland Field Manual which the state department, as well as an independent congressional inquiry, have alleged to be a Soviet forgery.[49] The State Department also highlighted the fact that, in the case of Richard Welch, "Grivas bizarrely accuses the CIA of playing a role in the assassination of one of its own senior officials" while "Sheepskin" couldn't have assassinated Stephen Saunders for the simple reason that, according to the US government, "the Greek government stated it dismantled the 'stay behind' network in 1988."[49] Netherlands Speculation that the Netherlands was involved in Gladio arose from the accidental discovery of large arms caches in 1980 and 1983.[50] In the latter incident, people walking in a forest near the village of Rozendaal, near Arnhem, chanced upon a large hidden cache of arms, containing dozens of hand grenades, semiautomatic rifles, automatic pistols, munitions and explosives.[51][52] That discovery forced the Dutch government to confirm that the arms were related to NATO planning for unorthodox warfare.[53] In 1990, then-Prime Minister Ruud Lubbers told the Dutch Parliament that his office was running a secret organisation that had been set up inside the Dutch defence ministry in the 1950s, but denied it was supervised directly by NATO or other foreign bodies. He went on to inform that successive prime ministers and defence chiefs had always preferred not to inform other Cabinet members or Parliament about the secret organization. It was modelled on the nation's World War II experiences of having to evacuate the royal family and transfer government to a government-in-exile,[52] originally aiming to provide an underground intelligence network to a government-in-exile in the event of a foreign invasion, although it included elements of guerilla warfare. Former Dutch Defence Minister Henk Vredeling confirmed the group had set up arms caches around the Netherlands for sabotage purposes.[52] Already in 1990, it was known that the weapons cache near Velp, while accidentally 'discovered' in 1983, had been plundered partially before. It still contained dozens of hand grenades, semiautomatic rifles, automatic pistols, munitions and explosives at the time of discovery, but five hand grenades had gone missing.[52] A Dutch investigative television program revealed on 9 September 2007, that another arms cache that had belonged to Gladio had been ransacked in the 1980s. It was located in a park near Scheveningen. Some of the stolen weapons, including hand grenades and machine guns, later turned up when police officials arrested criminals John Mieremet and Sam Klepper in 1991. The Dutch military intelligence agency MIVD feared at the time that disclosure of the Gladio history of these weapons would have been politically sensitive.[54][55] Norway In 1957, the director of the secret service NIS, Vilhelm Evang, protested strongly against the pro-active intelligence activities at AFNORTH, as described by the chairman of CPC: "[NIS] was extremely worried about activities carried out by officers at Kolsås. This concerned SB, Psywar and Counter Intelligence." These activities supposedly included the blacklisting of Norwegians. SHAPE denied these allegations. Eventually, the matter was resolved in 1958, after Norway was assured about how stay-behind networks were to be operated.[56] In 1978, the police discovered an arms cache and radio equipment at a mountain cabin and arrested Hans Otto Meyer (no), a businessman accused of being involved in selling illegal alcohol. Meyer claimed that the weapons were supplied by Norwegian intelligence. Rolf Hansen, defence minister at that time, stated the network was not in any way answerable to NATO and had no CIA connection.[57] Portugal Further information: Aginter Press In 1966, the CIA set up Aginter Press which, under the direction of Captain Yves Guérin-Sérac (who had taken part in the founding of the OAS), ran a secret stay-behind army and trained its members in covert action techniques amounting to terrorism, including bombings, silent assassinations, subversion techniques, clandestine communication and infiltration and colonial warfare.[12] Turkey Main article: Counter-Guerrilla See also: Ergenekon (allegation), Deep state in Turkey, 1980 Turkish coup d'état, and Ruzi Nazar In an excerpt from Mehtap Söyler's 2015 book entitled The Turkish Deep State: State Consolidation, Civil-Military Relations and Democracy, Söyler details how certain Western forces encouraged Turkish nationalism via Operation Gladio. Specifically, Operation Gladio empowered Turanism through the founding member of the Counter-Guerrilla; Alparslan Türkeş — a product of that CIA initiative.[58] As one of the nations that prompted the Truman Doctrine, Turkey is one of the first countries to participate in Operation Gladio and, some[who?] say, the only country where it has not been purged.[59] The counter-guerrillas' existence in Turkey was revealed in 1973 by then-prime minister Bülent Ecevit.[60] General Kenan Evren, who became President of Turkey following a successful coup d'état in 1980, served as the head of the Counter-Guerrilla, the Turkish branch of Operation Gladio. Historians and outside investigators have speculated that Counter-Guerrilla and several subordinate Intelligence, Special Forces, and Gendarmerie units were possibly involved in numerous acts of state-sponsored terrorism and engineering the military coups of 1971 and 1980. Many of the high ranking plotters of the 1971 and 1980 coup, such as Generals Evren, Memduh Tağmaç, Faik Türün, Sabri Yirmibeşoğlu, Kemal Yamak and Air Force Commander Tahsin Şahinkaya served at various times under the command of Counter-Guerrilla or the subordinate Tactical Mobilisation Group and Special Warfare Department. Additionally, the CIA employed people from the far-right, such as Pan-Turkist SS-member Ruzi Nazar (father of Sylvia Nasar),[61] to train the Grey Wolves (Turkish: Ülkücüler),[62] the youth wing of the MHP. Nazar was an Uzbek born near Tashkent who had deserted the Red Army to join the Nazis during World War II in order to fight on the Eastern Front for the creation of a Turkistan.[63] After Germany lost the war, some of its spies found haven in the U.S. intelligence community. Nazar was such a person, and he became the CIA's station chief to Turkey.[64]2.42K views 1 comment -

Operation Gladio Part 2: CIA, MI6, Subversive Activities & False Flag Operations