-

Volunteer Norwegian Legion - Narvik - Lebensborn - Finnish Winter War - Josef Terboven - Waffen SS

Military1945SUPPORT THE CHANNEL www.Patreon.com/Military1945 With the British pulling their troops out from the Norwegian theater in May of 1940 and the coming of the war against the Soviet Union, we’ll see how Nationalist Norway got involved in an uncomfortable slow-dance with their occupiers which made the creation of the volunteer Norwegian Legion possible. We’ll take a look at the well balanced propaganda campaign used to fine volunteers and get financial support from the general Norwegian public. Finally we’ll follow the unit as it musters for the first time and begins to train in preparation for its active duty in 1942. During the invasion of Denmark and Norway in 1940, Operation Weserübung, the horrors of the Polish campaign had not been experienced by the Scandinavian populations. Although the fighting lasted for 62 days, most of the combat took place away from the cities and there had been no significant bombing campaign, which left the general population largely unaffected. This footage is of German Fallschirmjäger, paratroopers, in an operation around Narvik a largely rural area situated far to the north. With the British pulling out for geopolitical reasons, namely the battle in France coming to a head, rather than being soundly defeated militarily there there was a lingering question as to whether they’d been abandoned.. As the German authority settled in, the soft policies associated to the country’s occupation were intentionally lenient and cooperative in nature. Unlike in most occupied countries German soldiers were encouraged to fraternize with the locals. 8 SS-administered so-called Lebensborn homes were set up in Norway which took care of thousands of children born from relationships between Norwegian women and German soldiers. Through 1940 and into 1941 news about the German military’s Blitzkrieg victories continued streaming in. As shown in this footage the presentation of captured enemy weaponry was popular, especially among the youth, and reinforced the idea of German military superiority. In addition, impressive military parades were regularly organized in the cities. There was an understandably large portion of the Norwegian population that believed the current situation was long-term or even permanent. Even the Norwegian government in exile in Britain was itself ambiguous about what they expected of their compatriots. In a speech by Norwegian Minister of Justice Terje Wold, broadcast by the BBC for listeners in German-occupied Norway it was declared that while the enemy holds power in the country, Norwegian public servants must endure a certain connection with the German authorities. But that a Norwegian public servant must never let himself be used as a tool by the German regime. That complicated relationship was left to the interpretation of each individual. Ever since the Russo-Finnish Winter War of 1939-40 there was considerable mistrust of the Soviets. With the invasion of the Soviet Union there was a general feeling that Norway needed to do its part in this anti-Bolshevik crusade. On July 4 in coordination between the German occupational authorities and the Norwegian fascist National Union that was lead by the collaborationist Quisling, former Norwegian soldiers were invited to join the new volunteer Norwegian Legion. Within a week 448, or 20%, of the Norwegian army’s former officers had volunteered. The successful recruiting campaign placed heavy emphasis on showing solidarity with Finnland. One way of doing this was by showing the two nations flags together. By portraying Germany as a comrade-in-arms, as an equal, once again a feeling of cooperation and not subservience was emphasized. The Norwegian Legion was officially part of the Waffen-SS however its commanding officers were to be Norwegian, the language spoken would be Norwegian, they were promised Norwegian uniforms, and their region of operation would supposedly of a defensive nature in Finnland. Everything pointed towards the revitalization of Norway by the newly empowered and seemingly independent, Norwegian nationalists. Those recruited to the Norwegian Legion were first sent to the Bjolsen Skole camp in Norway where uniforms were issued. This is also where they got their first surprise. Rather than receiving Norwegian uniforms as promise the Legionnaires received standard German SS uniforms. The only difference was the Norwegian national flag sleeve patch. To what extent the young soldiers could comprehend the significance of this sleight of hand is difficult to say. Had some innocent sounding supply snafu been used as an excuse? The unit was already officially incorporated into the SS hierarchy which put the soldiers ultimately under the direct command of the Reichsführer Heinrich Himmler. But this outwardly evident symbolic association was also meaningful. The official motto of Himmler’s SS was Meine Ehre heisst Treue, or Loyalty is my honor. The question of course was - loyalty to whom and for what?328 views 1 comment

Military1945SUPPORT THE CHANNEL www.Patreon.com/Military1945 With the British pulling their troops out from the Norwegian theater in May of 1940 and the coming of the war against the Soviet Union, we’ll see how Nationalist Norway got involved in an uncomfortable slow-dance with their occupiers which made the creation of the volunteer Norwegian Legion possible. We’ll take a look at the well balanced propaganda campaign used to fine volunteers and get financial support from the general Norwegian public. Finally we’ll follow the unit as it musters for the first time and begins to train in preparation for its active duty in 1942. During the invasion of Denmark and Norway in 1940, Operation Weserübung, the horrors of the Polish campaign had not been experienced by the Scandinavian populations. Although the fighting lasted for 62 days, most of the combat took place away from the cities and there had been no significant bombing campaign, which left the general population largely unaffected. This footage is of German Fallschirmjäger, paratroopers, in an operation around Narvik a largely rural area situated far to the north. With the British pulling out for geopolitical reasons, namely the battle in France coming to a head, rather than being soundly defeated militarily there there was a lingering question as to whether they’d been abandoned.. As the German authority settled in, the soft policies associated to the country’s occupation were intentionally lenient and cooperative in nature. Unlike in most occupied countries German soldiers were encouraged to fraternize with the locals. 8 SS-administered so-called Lebensborn homes were set up in Norway which took care of thousands of children born from relationships between Norwegian women and German soldiers. Through 1940 and into 1941 news about the German military’s Blitzkrieg victories continued streaming in. As shown in this footage the presentation of captured enemy weaponry was popular, especially among the youth, and reinforced the idea of German military superiority. In addition, impressive military parades were regularly organized in the cities. There was an understandably large portion of the Norwegian population that believed the current situation was long-term or even permanent. Even the Norwegian government in exile in Britain was itself ambiguous about what they expected of their compatriots. In a speech by Norwegian Minister of Justice Terje Wold, broadcast by the BBC for listeners in German-occupied Norway it was declared that while the enemy holds power in the country, Norwegian public servants must endure a certain connection with the German authorities. But that a Norwegian public servant must never let himself be used as a tool by the German regime. That complicated relationship was left to the interpretation of each individual. Ever since the Russo-Finnish Winter War of 1939-40 there was considerable mistrust of the Soviets. With the invasion of the Soviet Union there was a general feeling that Norway needed to do its part in this anti-Bolshevik crusade. On July 4 in coordination between the German occupational authorities and the Norwegian fascist National Union that was lead by the collaborationist Quisling, former Norwegian soldiers were invited to join the new volunteer Norwegian Legion. Within a week 448, or 20%, of the Norwegian army’s former officers had volunteered. The successful recruiting campaign placed heavy emphasis on showing solidarity with Finnland. One way of doing this was by showing the two nations flags together. By portraying Germany as a comrade-in-arms, as an equal, once again a feeling of cooperation and not subservience was emphasized. The Norwegian Legion was officially part of the Waffen-SS however its commanding officers were to be Norwegian, the language spoken would be Norwegian, they were promised Norwegian uniforms, and their region of operation would supposedly of a defensive nature in Finnland. Everything pointed towards the revitalization of Norway by the newly empowered and seemingly independent, Norwegian nationalists. Those recruited to the Norwegian Legion were first sent to the Bjolsen Skole camp in Norway where uniforms were issued. This is also where they got their first surprise. Rather than receiving Norwegian uniforms as promise the Legionnaires received standard German SS uniforms. The only difference was the Norwegian national flag sleeve patch. To what extent the young soldiers could comprehend the significance of this sleight of hand is difficult to say. Had some innocent sounding supply snafu been used as an excuse? The unit was already officially incorporated into the SS hierarchy which put the soldiers ultimately under the direct command of the Reichsführer Heinrich Himmler. But this outwardly evident symbolic association was also meaningful. The official motto of Himmler’s SS was Meine Ehre heisst Treue, or Loyalty is my honor. The question of course was - loyalty to whom and for what?328 views 1 comment -

Norwegen Legion Pt 2 - 2nd SS Brigade - Quisling - Heinrich Himmler - Waffen SS - Siege of Leningrad

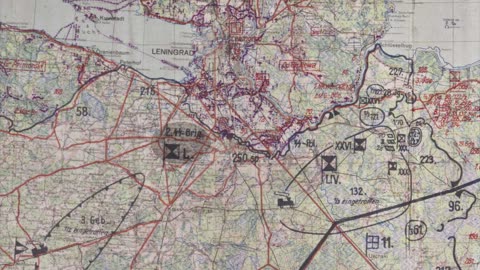

Military1945SUPPORT THE CHANNEL www.Patreon.com/Military1945 Today we’ll continue with part 2 of the Norwegian Legion series as we follow the unit through their basic training which had a strong emphasis on both physical fitness and political indoctrination. A series of bad decisions on on the part of the German High Command effected the moral of the Legion and eventually caused their originally successful recruitment campaign to stall. With basic training completed the unit was finally ready for active duty; their assigned region of deployment would come as a nasty surprise. To entice new recruits, they were signing short 3-month trial enlistments. The unit was being billed by Norwegian fascist Quisling as the new Norwegian army and it had been intended to be organized as such. Those that had military experience in the former Norwegian army were especially interesting to the Germans. On 29 July 1941, the first 300 Norwegian volunteers arrived in Kiel, Germany, and were then sent on to Fallingbostel Training Camp for basic training. By the end of August the total number of recruits had grown to over 700 and by the end of 1941, it had the strength of 1218 men with an additional reserve battalion provided for replacement. That it was quietly placed within the hierarchy of Himmler’s SS and issued standard SS rather than Norwegian uniforms was an unpleasant surprise to some but the truth is, most decided reenlist anyway. In order to join the Norwegian Legion, the volunteers needed to prove their nordic ancestry and be free of physical disabilities. The relatively limited amount of advanced military training was meant to be compensated by a heavy focus on physical fitness and ideological indoctrination. They were being trained to operate as aggressive assault infantry, or Stosstruppen. As stated in a Waffen SS training manual “Sport arouses belligerence, hardens the will, promotes self-discipline, and therefore promotes the training of the SS man to the level of a combat-effective fighter. The indoctrination was based on the National Socialist worldview which pitted the idealized Germanic and Nordic cultures and the supposedly superior Arian gene-pool against barbaric and inferior Judeo-Bolshevism. It was a kind of ideological religion where loyalty, courage and self-sacrifice were the commandments; disloyalty was the worst “sin”. The war in the east was presented as a crusade; a fight to the death between the forces of good and evil. The SS had planned to form a full German-style infantry regiment of 3 brigades with historic Norse names. The first named Viken with the majority of the recruits coming from the Oslo area, the second would be called Gula and the third Frosta. The recruiting campaign that had started out so well had lost some of its shine. Among the volunteers it became common knowledge that the German High command fully expected the war against the Soviet Union to be over by Christmas which left the future of the Legion in question. The Legion’s officers and NCOs were all Norwegians, but German advisors were detailed to our units. Officially they had no command authority, but some of them tried to acquire some, which caused a considerable amount of friction. In addition, the majority of the equipment and weaponry being issued, none of which being heavy, was either old or captured. Clearly, rather than being made into an effective frontline fighting force the unit was being used entirely for its propaganda value. By the end of 1941 hundreds of men were leaving as soon as their initial three-month term was up, including their first commander, the Norwegian Army Colonel Finn Hannibal Kjelstrup. Kjelstrup’s place was taken by the Viken battalion commander, Jørgen Bakke, but within two weeks he too resigned in disgust. The unanimously unpopular decisions had a materially negative effect on the influx of new recruits. Due the lack of volunteers the Gula and Frosta brigades would never be formed. Not until December of 1941 was much needed stability brought to the Legion when the Norwegian ex-Calvalry officer Artur Qvist took over its leadership. Then, eight months after the Norwegian Legion’s formation, with basic training completed, everything suddenly fell into place. There was an excitement in the air as the exact location as to where the unit was be be deployed had been kept a secret. In February of 1942 a fleet of Ju-52 transport planes arrived to the Fallingbostel training camp and literally, as the soldiers were being loaded on, they learned that rather than being deployed in Finnland as promised, they were being flown to the northeast over the occupied Baltic States and would take up positions in the zig zag of trenches around the besieged city of Leningrad. In addition, they would be under the command of German officers as part of the 2nd. SS Brigade. Any illusion that the young legionnaires might still have had, now most certainly must fallen away completely.319 views 1 comment

Military1945SUPPORT THE CHANNEL www.Patreon.com/Military1945 Today we’ll continue with part 2 of the Norwegian Legion series as we follow the unit through their basic training which had a strong emphasis on both physical fitness and political indoctrination. A series of bad decisions on on the part of the German High Command effected the moral of the Legion and eventually caused their originally successful recruitment campaign to stall. With basic training completed the unit was finally ready for active duty; their assigned region of deployment would come as a nasty surprise. To entice new recruits, they were signing short 3-month trial enlistments. The unit was being billed by Norwegian fascist Quisling as the new Norwegian army and it had been intended to be organized as such. Those that had military experience in the former Norwegian army were especially interesting to the Germans. On 29 July 1941, the first 300 Norwegian volunteers arrived in Kiel, Germany, and were then sent on to Fallingbostel Training Camp for basic training. By the end of August the total number of recruits had grown to over 700 and by the end of 1941, it had the strength of 1218 men with an additional reserve battalion provided for replacement. That it was quietly placed within the hierarchy of Himmler’s SS and issued standard SS rather than Norwegian uniforms was an unpleasant surprise to some but the truth is, most decided reenlist anyway. In order to join the Norwegian Legion, the volunteers needed to prove their nordic ancestry and be free of physical disabilities. The relatively limited amount of advanced military training was meant to be compensated by a heavy focus on physical fitness and ideological indoctrination. They were being trained to operate as aggressive assault infantry, or Stosstruppen. As stated in a Waffen SS training manual “Sport arouses belligerence, hardens the will, promotes self-discipline, and therefore promotes the training of the SS man to the level of a combat-effective fighter. The indoctrination was based on the National Socialist worldview which pitted the idealized Germanic and Nordic cultures and the supposedly superior Arian gene-pool against barbaric and inferior Judeo-Bolshevism. It was a kind of ideological religion where loyalty, courage and self-sacrifice were the commandments; disloyalty was the worst “sin”. The war in the east was presented as a crusade; a fight to the death between the forces of good and evil. The SS had planned to form a full German-style infantry regiment of 3 brigades with historic Norse names. The first named Viken with the majority of the recruits coming from the Oslo area, the second would be called Gula and the third Frosta. The recruiting campaign that had started out so well had lost some of its shine. Among the volunteers it became common knowledge that the German High command fully expected the war against the Soviet Union to be over by Christmas which left the future of the Legion in question. The Legion’s officers and NCOs were all Norwegians, but German advisors were detailed to our units. Officially they had no command authority, but some of them tried to acquire some, which caused a considerable amount of friction. In addition, the majority of the equipment and weaponry being issued, none of which being heavy, was either old or captured. Clearly, rather than being made into an effective frontline fighting force the unit was being used entirely for its propaganda value. By the end of 1941 hundreds of men were leaving as soon as their initial three-month term was up, including their first commander, the Norwegian Army Colonel Finn Hannibal Kjelstrup. Kjelstrup’s place was taken by the Viken battalion commander, Jørgen Bakke, but within two weeks he too resigned in disgust. The unanimously unpopular decisions had a materially negative effect on the influx of new recruits. Due the lack of volunteers the Gula and Frosta brigades would never be formed. Not until December of 1941 was much needed stability brought to the Legion when the Norwegian ex-Calvalry officer Artur Qvist took over its leadership. Then, eight months after the Norwegian Legion’s formation, with basic training completed, everything suddenly fell into place. There was an excitement in the air as the exact location as to where the unit was be be deployed had been kept a secret. In February of 1942 a fleet of Ju-52 transport planes arrived to the Fallingbostel training camp and literally, as the soldiers were being loaded on, they learned that rather than being deployed in Finnland as promised, they were being flown to the northeast over the occupied Baltic States and would take up positions in the zig zag of trenches around the besieged city of Leningrad. In addition, they would be under the command of German officers as part of the 2nd. SS Brigade. Any illusion that the young legionnaires might still have had, now most certainly must fallen away completely.319 views 1 comment