Premium Only Content

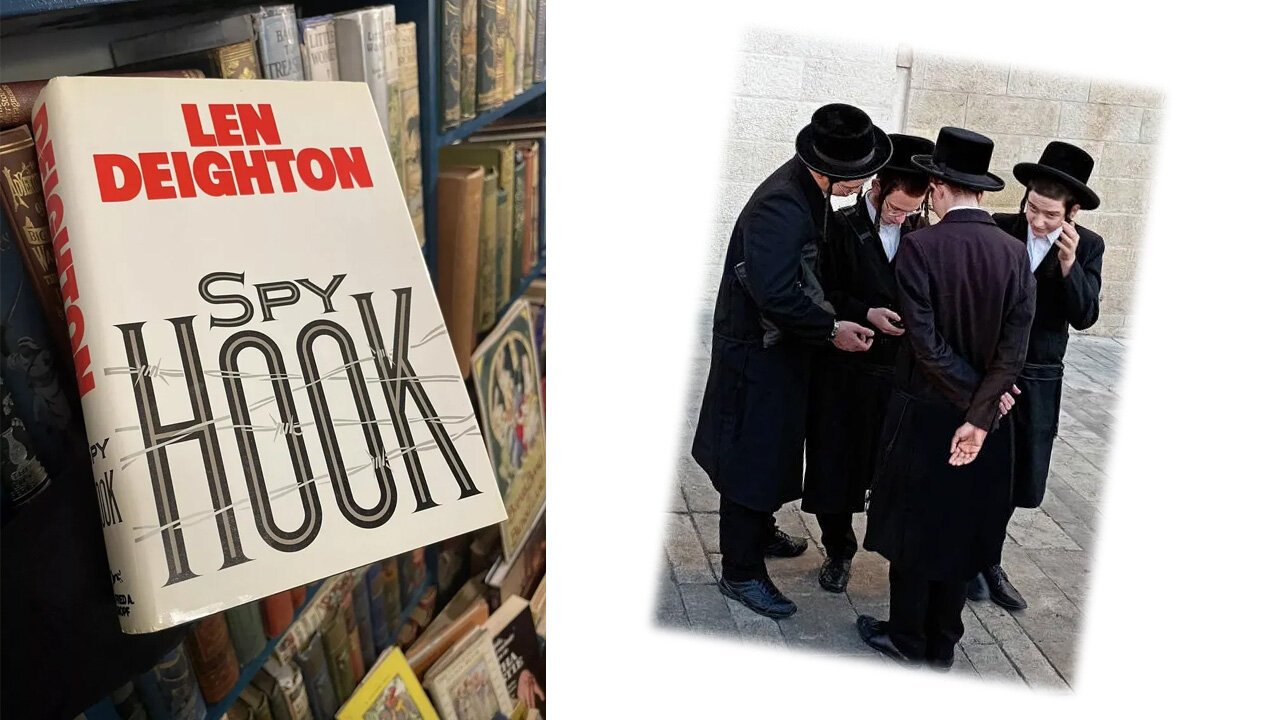

'Spy Hook' (1988) by Len Deighton

Len Deighton’s, 'Spy Hook' (1988) is the opening salvo in the second Bernard Samson trilogy, a continuation of the sprawling espionage saga that began with 'Berlin Game', 'Mexico Set', and 'London Match'. Deighton’s masterful return to Samson’s world is not just a reunion with a beloved character—it’s a reckoning. Whereas the first trilogy culminated in betrayal and the collapse of trust, 'Spy Hook' opens with the lingering damage: a disoriented and wounded protagonist trying to make sense of the ruins around him.

The novel finds Bernard Samson, former MI6 field agent and reluctant office man, psychologically adrift. His wife, Fiona, is revealed to be a double agent—an upper-class defector to East Germany whose betrayal continues to haunt Bernard. 'Spy Hook 'is a cold, paranoid novel, heavy with the weight of secrets and emotional fatigue. It is also a quiet novel by spy standards: there are no gunfights, few chases, and little in the way of glamorous espionage action. Instead, the thrills are cerebral and psychological. The real suspense lies in decoding motives, uncovering layers of lies, and surviving the slow strangulation of bureaucracy and institutional mistrust.

Bernard is tasked with investigating financial irregularities in the Service’s funding—an innocuous assignment that unfolds into a sinister web. As he follows the trail, he unearths hints of a possible conspiracy within MI6 itself. His search leads him to Los Angeles, Zurich, Paris, and Berlin, but the geography is less important than the mental terrain. Deighton is interested in showing us a world where loyalty is conditional, identity is unstable, and truth is always out of reach.

What makes 'Spy Hook' exceptional is Deighton’s absolute command of tone. He renders Samson’s world in greyscale: drab offices, bitter conversations, long walks through sleet-blasted streets. This is the anti-Bond novel. The women are complex and morally ambiguous, the men broken or compromised. Even Bernard himself is not particularly heroic—he is moody, frequently bitter, a man increasingly unsure of whether he is the player or the pawn. And yet, for all his cynicism, there is a kind of buried nobility to him. He wants to protect his children, salvage his dignity, and, perhaps naively, find answers in a world designed to obscure them.

Deighton’s writing is as clipped and cynical as ever. The dialogue brims with dry wit and menace. There is a kind of deadpan poetry in the way characters obliquely reveal their wounds. The pacing is slow, but deliberately so—it mirrors the grinding, wearying process of intelligence work. The novel is also a meditation on institutional decay: how secrets curdle, how loyalties erode, and how even the most capable agents are sacrificed by systems that demand obedience over competence.

In 'Spy Hook', Deighton continues his brilliant subversion of the spy genre. Instead of clear-cut heroes and villains, we get moral murk, emotional devastation, and the haunting knowledge that espionage doesn’t just destroy nations—it destroys people. It is not a standalone novel, but rather the beginning of a slow-burning arc that won’t pay off until the end of Spy Sinker, the final book in this second trilogy. But as a piece of spy fiction, 'Spy Hook' is both elegant and unnerving—a story not of action, but of erosion, where the question is not who is lying, but whether the truth matters anymore.

In short, 'Spy Hook' is a sophisticated, introspective thriller for readers who value psychological depth over pulp sensationalism. It confirms Deighton’s place not just as a spy writer, but as a chronicler of Cold War disillusionment, bureaucracy, and the personal costs of betrayal.

-

33:30

33:30

The Bryce Eddy Show

4 days ago $0.03 earnedMonty Bennett: HERO Model to Fight Crime

8.15K1 -

0:41

0:41

Living Your Wellness Life

3 days agoThe Prime-Years Transition

1.01K -

LIVE

LIVE

The Bubba Army

21 hours agoJimmy Kimmel's Back - Bubba the Love Sponge® Show | 9/23/25

2,497 watching -

34:15

34:15

Actual Justice Warrior

2 days agoIlhan Omar CHEERS Charlie Kirk's Murder

49K72 -

12:13

12:13

itsSeanDaniel

1 day agoMAGA Senator STANDS UP for Charlie Kirk and Free Speech

31.9K21 -

30:39

30:39

Comedy Dynamics

1 month agoBest of Jim Breuer: And Laughter for All

128K4 -

2:56:22

2:56:22

FreshandFit

14 hours agoDo Black People Deserve Reparations? DEBATE With Woman Propaganda.

200K191 -

1:58:26

1:58:26

Badlands Media

17 hours agoBaseless Conspiracies Ep. 151: Netanyahu, Dual Loyalties, and the Kirk Connection

50.1K33 -

4:55:05

4:55:05

Akademiks

10 hours agoYoung Thug Dissing YFN Lucci. Ready to Go back to Jail. Offset vs Cardi b

74.4K4 -

2:02:45

2:02:45

Inverted World Live

11 hours agoIs the Rapture Tomorrow? | Ep. 111

128K48