Premium Only Content

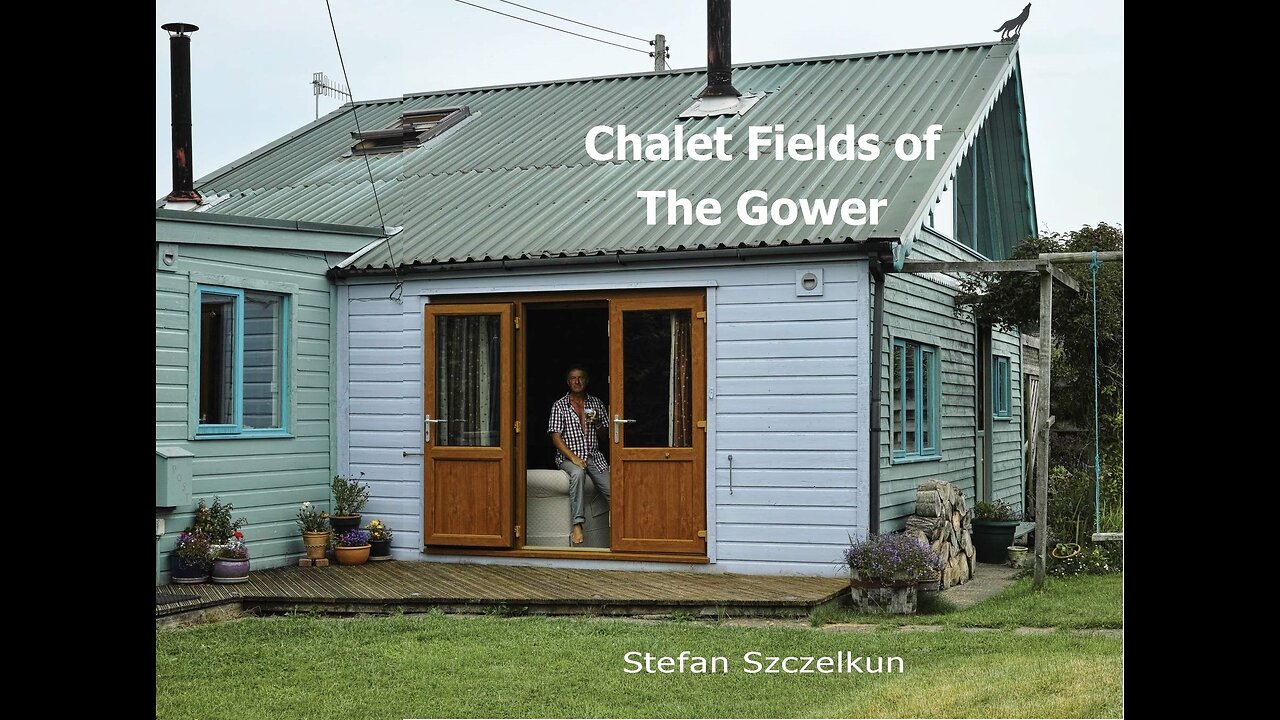

UK Forgotten Self-Building Tradition with Stefan Szczelkun on 1920-30s Plotlands, Shepperton & Gower

For more than a decade we – photographer Jason Orton and writer Ken Worpole – have documented the changing landscape and coastline of Essex and East Anglia, particularly its estuaries, islands and urban edgelands. We continue to explore many aspects of contemporary landscape topography, architecture and aesthetics, and in 2013 published our second book, The New English Landscape (Field Station | London, 2013), the second edition of which was published in 2015 and is now out of print.

https://thenewenglishlandscape.wordpress.com/2020/11/02/down-by-the-river/

Set amongst the houseboat community on the Thames near Fulham, A.P.Herbert’s popular 1930 novel, The Water Gypsies, portrayed a collection of people at odds with society. The main characters still worked the river as bargees, having spent all their lives with their families on the water, but others had adopted life on water as an escape. Living on or close by rivers was long associated with poverty and bohemian marginality and this theme is taken up and demonstrated in Stefan Szczelkun’s delightful photographic pocket-book, Plotlands of Shepperton, just published.

Stefan grew up in Shepperton and in 1966 and studied architecture in Portsmouth. I suspect his interest in vernacular architecture over-rode a concern with standard architectural forms and theories. Given that he was also a musician who once toured with the wildly experimental Scratch Orchestra in the early 70s, it was not surprising to read that he describes the self-built riverside chalets as being ‘the architectural equivalent of improvised music.’..

Plotlands – the struggle for land and affordable housing – the informally-planned settlements of self-built bungalows, chalets and shanties that gave working class families affordable access to rural and seaside property between the wars – are a distinctive feature of the British landscape and a living reminder of struggles over planning and property rights.

https://criticalplace.org.uk/2023/07/17/plotlands-the-struggle-for-land-and-affordable-housing/

It was the ability to build your own home affordably, adding to it over the years as income allowed, that motivated working class families to acquire plots of land, initially for weekend and holiday use, in nearly 300 plotland sites, many still flourishing today. These plotlands were seen by their residents as the real garden villages, settlements organised and run by mutual aid and collective action, where the benefits of rural living could be enjoyed by families escaping from city slums, and a house in the country could become a realistic ambition for otherwise property-less people.

Aided by new rail access to country and coast, with legislation in 1938 providing holidays with pay, working class households bought plots of poor quality marginal land at auction to build their holiday homes. The homes they erected on these plots were initially tents, huts or old railway carriages. They were single-storey houses, simply built from whatever material (corrugated iron, asbestos, pre-cast concrete and bricks) lay at hand. The homesteaders cycled from the station with building materials strapped to their backs, turning their labour into capital, and extending their self-built homes as their income allowed.

While the self-made resort of Peacehaven is now indistinguishable from any other seaside town, the characterful riverside homes at Bewdley on the banks of the Severn continue to excite architectural interest, while plotlands at Dungeness and at Humberston near Cleethorpes, are now protected as conservation areas. The plotlands at Laindon in Essex housed a settled population of 25,000 in the 1940s, served by 75 miles of grass-track roads, with no sewers and just standpipes for water supply. Incorporated into Basildon new town, this informally planned settlement is now a nature reserve and houses the Dunton Hills Plotland museum, while on the outskirts of other Essex towns, the irregular landscape of plotlands is still visible, and shacks and chalets persist in the haphazard scattering of more ostentatious self-built homes along a grid-iron pattern of unadopted roads.

It was to cleanse the landscape of these self-built settlements that the 1947 town planning legislation was created.

Colin Ward and Dennis Hardy, whose research has saved Plotlands from the oblivion of official planning histories, liken these self-build towns to the informal settlements of the Global South, where mutual aid and self-organisation challenge the urban landscapes of exclusion and eviction. In Jaywick Sands, for example, the Plotlanders planned and ran their own town, erecting street lighting from their own subscriptions, building their own flood protection, and running their own sewage disposal service.

-

LIVE

LIVE

SOLTEKGG

2 hours ago🔴LIVE - Battlefield 6 REDSEC (30+ KILL WORLD RECORD)

82 watching -

50:26

50:26

BonginoReport

9 hours agoElections Post-Mortem with Mayor Scott Singer - Nightly Scroll w/ Hayley Caronia (Ep.174)

75.4K22 -

LIVE

LIVE

XDDX_HiTower

2 hours agoARC RAIDERS, FIRST DROP IN

59 watching -

LIVE

LIVE

Eternal_Spartan

11 hours ago🟢 Eternal Spartan Plays Resident Evil 8 | USMC Veteran

48 watching -

45:54

45:54

Donald Trump Jr.

7 hours agoGood Luck Chuck! The Left Lashes Out Over Shutdown Scheme's Failure | Triggered Ep.290

113K81 -

LIVE

LIVE

Fragniac

3 hours ago🔵🟢🟡🔴 LIVE - FRAGNIAC - ARC RAIDERS - in Search of THE CLIP ( -_•)▄︻テحكـ━一💥

38 watching -

1:00:25

1:00:25

BIG NEM

8 hours agoDajana Gudic: Surviving the Bosnian War to Woke California

9.55K -

13:09:38

13:09:38

LFA TV

1 day agoLIVE & BREAKING NEWS! | MONDAY 11/10/25

155K35 -

22:01

22:01

Jasmin Laine

7 hours agoCBC Host ABRUPTLY ENDS Interview After Guest Says: “That Isn't True”

25K10 -

1:20:47

1:20:47

Kim Iversen

5 hours agoMAGA = Make Antisemitism Great Again?

136K155